Rights group says 20 missing after deadly Indonesia protests

Maltese NGOs Rally Solidarity as Rights Group Reports 20 Missing After Deadly Indonesia Protests

By Lara Pace, Valletta

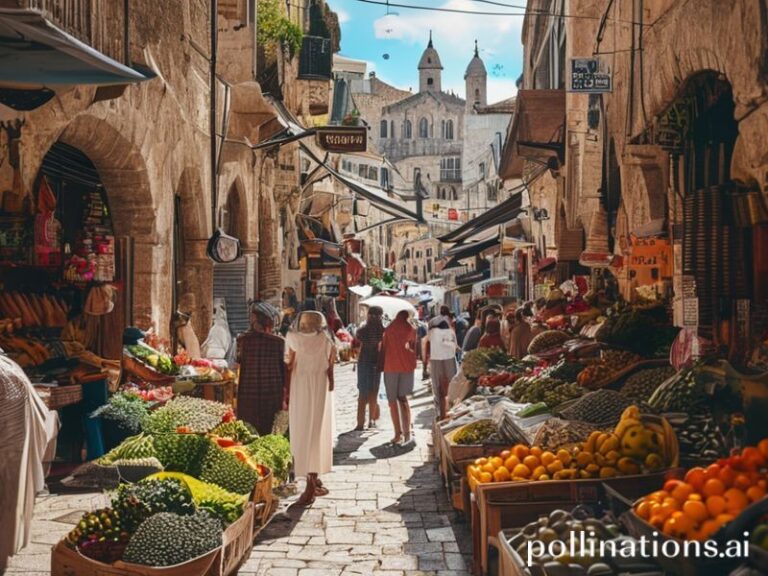

As the last ferry from Gozo glided into Ċirkewwa on Monday evening, mobile phones across Malta lit up with grim headlines: at least 20 Indonesian students and labour activists have vanished following violent protests in Jakarta. The alert, issued by Jakarta-based rights coalition KontraS, has stirred a wave of concern in Malta, where centuries-old maritime ties to Southeast Asia run deeper than most islanders realise.

From the shaded courtyards of the Jesuit-run St Aloysius College to the sun-baked shipyards of Marsa, the news feels close to home. Malta’s own history of protest—from the 1919 Sette Giugno riots that left four dead to the 1989 University uprising that hastened the end of Mintoff’s domination—makes the Indonesian disappearances resonate here. “When young people disappear after standing up to power, Maltese hearts skip a beat,” says Dr Maria Camilleri, coordinator of aditus foundation, one of the island’s leading human-rights NGOs. “We know what it is to be a small voice shouting into the wind.”

KontraS claims the missing were last seen on Wednesday night as Indonesian police and army units dispersed a peaceful rally against a controversial new labour law. At least six demonstrators are confirmed dead, scores injured, and the whereabouts of 20 others—mostly university students and gig-economy riders—remain unknown. Indonesian authorities deny any knowledge of detentions, but WhatsApp messages shared with Hot Malta show panicked students telling friends they were being “loaded into unmarked vans.”

The Maltese connection begins with people, not politics. Roughly 1,200 Indonesian nationals live in Malta today: chefs in Paceville kitchens, seamen on LNG tankers berthed at Delimara, and care-workers who sing lullabies in Bahasa to elderly residents of St Vincent de Paul. Many send part of their paycheck back to siblings studying in Jakarta or Bandung. “My brother was on that march,” says Fitri Andriyanto, a 27-year-old cook at a Sliema bistro, voice cracking over a hurried cigarette break. “He messaged me ‘Wish me luck’ at 6 p.m. Wednesday. Nothing since.” Fitri has joined a hastily-formed Indonesian-Maltese Solidarity Group that meets nightly on Zoom, swapping updates and drafting letters to the Indonesian embassy in Rome.

Malta’s tight-knit activist scene has responded with characteristic speed. Moviment Graffitti hung a banner reading “20 Missing—No Silence” from the Sliema ferries jetty at dawn today, forcing commuters to confront the issue before their first espresso. Meanwhile, the University of Malta’s Students’ Futsal Club has pledged to dedicate this weekend’s Inter-Faculty tournament to the disappeared, printing their names on the back of every jersey. “Our grandparents survived war; our parents marched for freedom,” says club president Karl Briffa. “The least we can do is kick a ball in someone else’s name.”

Cultural echoes abound. The Indonesian shadow-puppet theatre of wayang kulit—where silhouettes flicker on linen screens—feels oddly familiar to Maltese who grew up with the folk-figure Il-Maqluba looming in village pageants. Both traditions remind viewers that darkness can obscure, but also reveal. In that spirit, local theatre troupe Troupe 18 will stage a candle-lit reading of Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar’s “Aku” at the Upper Barrakka Gardens tomorrow evening, inviting passers-by to record 20-second video messages of solidarity that will be stitched into a single clip sent to KontraS.

For Malta’s business community, the crisis carries practical weight too. Enemalta is negotiating a liquefied-natural-gas deal with Indonesian supplier Pertamina; the Chamber of Commerce has urged government to add a human-rights clause to any future accord. Tourism Minister Clayton Bartolo, fresh from inaugurating the new Malta-Indonesia direct flight route scheduled for 2025, faces calls to freeze promotional campaigns until the 20 are accounted for. “We can’t market Bali sunsets while Bali students disappear,” insists activist Mandy Micallef, collecting signatures outside Parliament this morning.

Back in Gżira, Fitri clutches his phone, waiting for the screen to light up with news. “Malta gave me a job, a community, and now a voice,” he says. “I just want to use it to find my brother.” As the bells of the Basilica of Ta’ Pinu echo across the harbour, they carry a Maltese plea across two oceans: bring them home.