€250-a-Month Flats in Marsa: How YMCA’s Radical Housing Scheme Is Reigniting the Maltese Dream

Affordable housing scheme ‘represents hope’ – YMCA

—————————————————

By Luke Zahra | Hot Malta

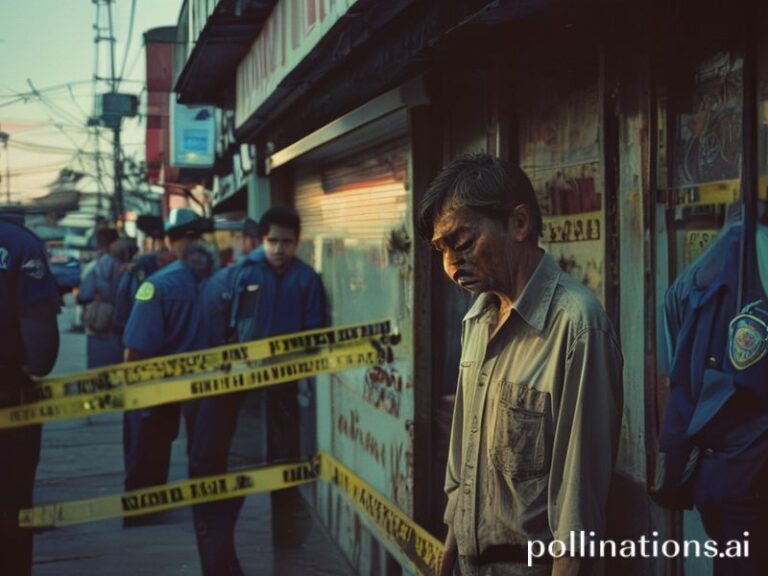

On the narrow, sun-baked streets of Marsa’s Dock One estate, where drying laundry flaps from every balcony and children chase footballs across cracked pavements, a modest block of flats is about to become the unlikely stage for Malta’s newest social experiment. Later this month, the YMCA Malta will hand over the keys to 18 fully refurbished units, each priced at €250 a month – roughly the cost of a long-weekend Airbnb in neighbouring Sliema.

For the NGO, the scheme is more than bricks and mortar; it is a direct answer to the island’s spiralling rent crisis. “This is not charity,” insists CEO Anthony Camilleri, surveying the freshly painted façade. “It is dignity. These flats represent hope for people who believed the Maltese dream had forgotten them.”

The numbers are stark. National Statistics Office data released last week show that average rents have jumped 42 % since 2019, while minimum wage has crept up only 8 %. In Valletta and St Julian’s, studio apartments now command €1,200 monthly – forcing low-paid hospitality staff, cleaners and carers to double-up in overcrowded rooms or move back in with parents. Against that backdrop, a €250-a-month flat sounds almost folkloric.

Yet the story begins not in a boardroom but in a parish hall in Ħamrun, where YMCA volunteers were serving soup to migrants sleeping rough in the old railway tunnels. Camilleri recalls one man from Gambia, a trained mechanic, who asked only for “a place to keep my tools and my pride.” The encounter spurred a frantic search for unused public property. They found it in the Dock One estate: three derelict floors once slated for demolition, now retrofitted with solar panels, grey-water systems and communal roof terraces overlooking the Grand Harbour.

The government provided a 30-year emphyteutical lease for one symbolic euro; the EU Social Cohesion Fund chipped in €1.2 million. Local contractors donated tiles and plumbing fixtures; Gozitan craftsmen installed traditional xorok balconies, blending contemporary insulation with Maltese limestone aesthetics. “We wanted residents to feel they belong to this island, not just occupy a box,” explains architect Maria Pace, who oversaw the retrofit.

Inside, the flats are compact but clever: fold-down beds, reclaimed ship-wood counters, sea-blue tiles that echo the nearby creeks. Each resident – single parents, ageing pensioners, former prisoners, foreign workers – receives a three-year lease, renewable if they enrol in YMCA upskilling courses ranging from English literacy to forklift certification. “Housing without pathways is just warehousing,” Camilleri says.

The cultural resonance is unmistakable. For centuries, Malta’s limestone towns have been built on the principle of *qaghqa tal-ghaqda* – the bread of togetherness – where extended families lived under one roof. Yet mass tourism and Airbnbs hollowed out neighbourhoods, converting grandmother’s flat into a stag-party crash pad. The YMCA model offers a modern twist on that old communal spirit: shared courtyards, roof allotments, and a ground-floor café run by residents that will serve ftira and Somali chai side by side.

Community impact is already visible. Downstairs, former Dock One resident Etienne Micallef, 63, who once queued at the YMCA food bank, now manages the building’s maintenance schedule. “I was born in this street when it smelled of diesel and fish,” he says, wiping grit from his hands. “Now it smells of fresh paint and possibility.” Next door, Eritrean mother-of-two Selam Tesfay studies Maltese verb tables while her son kicks a ball against a mural painted by art students from MCAST. “My kids say this is the first place that feels like home,” she smiles.

Not everyone is convinced. Some Marsa shopkeepers fear the project will attract “more foreigners”, a coded anxiety in a country where 27 % of residents are non-Maltese. Yet a recent University of Malta survey found 68 % of locals support social housing if it “mixes communities rather than ghettoises them.” The YMCA’s open-door policy – Sunday rooftop film nights, Maltese language drop-ins – aims to turn sceptics into neighbours.

With 3,000 more units needed nationwide, Camilleri admits the scheme is a drop in the Mediterranean. But he hopes it will ripple. “If Dock One can work, why not Cottonera, or Żejtun, or a vacant hotel in Buġibba?” He gestures toward the harbour where cruise ships loom like floating apartment blocks. “We cannot out-build the market, but we can out-imagine it.”

As the sun dips behind the bastions, residents begin lighting up the new flats like small lanterns against the limestone. Somewhere on the third floor, a guitar strums the opening chords of *Għana tal-Poplu*. Hope, it turns out, has a Maltese soundtrack.