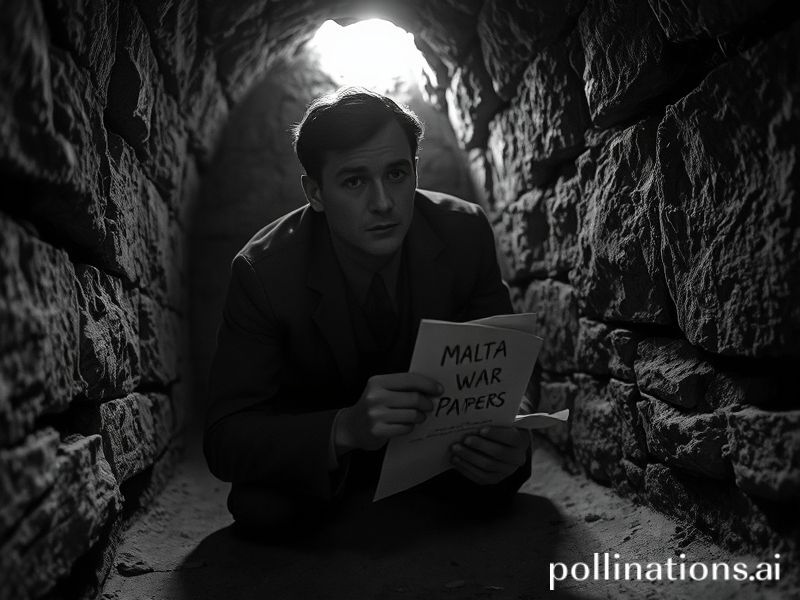

From Kinnie Labels to George Cross: Malta War Papers Reveal Untold Stories of Island Courage

The Malta War Papers – Chronicles of Courage

By Luke Vella, Valletta

A single, yellowing envelope stamped “On His Majesty’s Service – 1942” has just landed on the desk of the National Archives in Rabat. Inside: a letter from 19-year-old Carmelo Zahra, RAF ground-crew, scribbled on the back of an empty Kinnie label. “If I don’t make it, tell Nanna the lamp can go to Ċensa next door.” That scrap of paper is page one of the newly released Malta War Papers – Chronicles of Courage, a 4,000-document trove that is already reshaping the way Maltese see their own wartime story.

Unlike the polished histories written by British generals, these papers are raw, intimate, overwhelmingly Maltese. There are diary fragments in dialect (“Il-ġurnata sħuna, il-ħoss ta’ bomba qisu qalbna”), ration cards reused as children’s colouring books, and a hand-drawn map of a Mellieħa field where a farmer buried his goats to save them from Luftwaffe strafing. Together they form a mosaic of ordinary courage that official narratives rarely capture.

Local context

Between 1940 and 1943 Malta endured 3,000 air raids. The George Cross awarded to the entire island is often quoted, yet the daily texture of life under siege has remained fragmented. Dr Maria Camilleri, lead archivist on the project, explains: “We always knew the statistics; now we have the voices.” The papers were discovered last winter when workers renovating a Birkirkara townhouse lifted a floorboard and found a biscuit tin stuffed with letters. Further searches in Rabat attics, Mosta churches and even the dusty loft of the Phoenicia Hotel turned up more bundles, all handed over voluntarily by families who feared the papers would otherwise be lost to humidity and time.

Cultural significance

In a country where festa fireworks still echo the sounds that once meant death, memory is visceral. The Chronicles give that memory new colours. One entry records how the village band of Żebbuġ played the hymn “Maria, Ħenn Għalina” during an all-clear at 3 a.m., prompting neighbours to open their doors and sing along, blackout be damned. Another note, from a Senglea dockworker, lists the nicknames locals gave to incoming aircraft: “Il-Bug” for the lumbering Sunderland, “Tikka-Tikka” for the Messerschmitt’s guns. These details are gold for linguists tracking how Maltese absorbed Italian, English and fear into a single tongue.

The papers also highlight women’s hidden roles. A 1941 ledger kept by the Għaxaq Women’s Institute logs 11,000 bandages rolled from old wedding sheets; beside it, a teenager’s sketch portrays her mother rolling pastry with one hand while cradling a neighbour’s baby in the other. “For the first time we see the siege through Maltese women’s eyes,” says historian Prof. Carmen Sammut. “Their courage wasn’t in medals, but in stubborn daily survival.”

Community impact

Within 48 hours of the exhibition opening at MUŻA last Friday, queues snaked around Republic Street. Visitors linger longest at the interactive map where they can pin the address of a grandparent who served or sheltered. By Monday, 3,200 pins dotted the islands from Għarb to Marsaxlokk, turning the map into a constellation of private memories now publicly shared.

Schools have already requested 50 travelling suitcases – replicas of the biscuit tin – filled with high-resolution copies so children can handle history. A Gozitan teacher told me her Year 6 pupils gasped when they recognised the same type of Kinnie label their grandparents still use as bookmarks. “Suddenly 1942 isn’t black-and-white,” she said. “It’s fizzy and orange.”

Tourism Malta is studying evening “Siege Walks” where actors read excerpts by lantern light in the silent streets of Birgu. Meanwhile, local cafés are reporting a spike in sales of ftira tal-ħobż biż-żejt after a 1943 diary entry describing the sandwich as “the taste of peace when the sirens stop.”

Conclusion

The Malta War Papers – Chronicles of Courage do more than commemorate; they reclaim. They pull the wartime narrative out of London’s Cabinet War Rooms and plant it firmly in Maltese kitchens, fields and band clubs. In doing so, they remind us that courage is not only the stuff of statues and ceremonies; sometimes it is a teenager writing home on a Kinnie label, promising Nanna the lamp will find the right hands. Seventy-eight years later, that promise has been kept – and our islands shine brighter for it.