Rare Siġġiewi vintage photos unveiled: 120 images tracing Malta village life from 1868 to 1962

In pictures: Siġġiewi in old photographs – a village that time forgot to erase

By Hot Malta staff

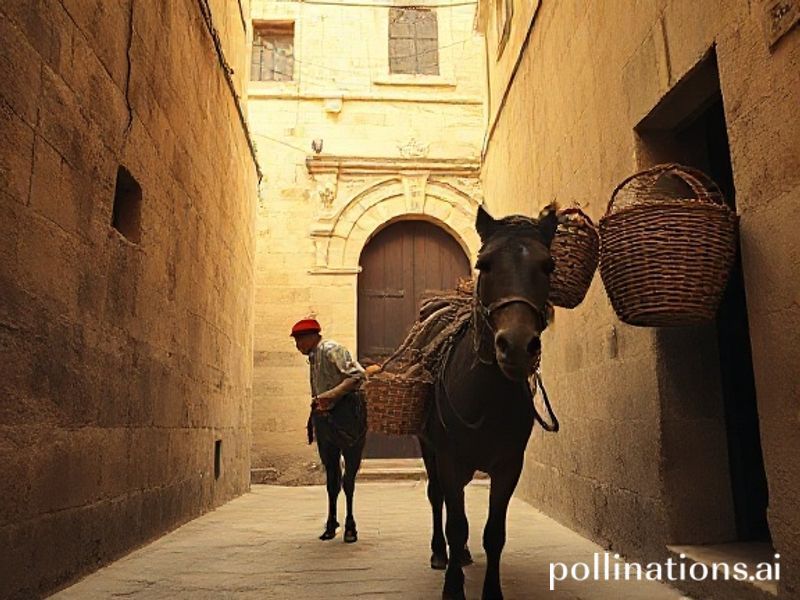

The first thing that hits you is the silence. Not the hush of a library, but the particular quiet of a limestone alley at siesta-time in 1954, caught by the lens of the late Siġġiewi photographer Ġużeppi Briffa. In the monochrome frame, a single donkey cart stands outside what is now the popular tavern ‘La Ta’ Rocco’, its driver shading his eyes from a sun we can almost feel. The cobbles are the same ones tourists trip over today, yet the absence of parked cars, neon signs or even plastic bollards makes the scene feel like a film still rather than lived reality.

That photograph is one of 120 newly digitised prints unveiled last weekend in the Siġġiewi parish hall, part of a crowd-sourced project cheekily titled “Żmien li Raba’ Qalbna” – times that took root in our hearts. Curators Marisa and Kurt Camilleri, a niece-and-nephew team who inherited dusty suitcases from three generations of village shutter-bugs, spent 18 months scanning, geo-tagging and interviewing elders to put names to faces and corners. The result is a chronological mosaic that begins with the earliest known image of Siġġiewi – an 1868 albumen print of St Nicholas’ collegiate church when its belfry was still topped by a temporary timber crane – and ends with the village’s first carnival float powered by a borrowed Lija fireworks generator, 1962.

For non-Siġġiewiani, the exhibition is a crash-course in micro-history. You learn that the village’s nickname “Ħal Xluq” (the bend) refers to the sharp dog-leg the main road once took to avoid a field belonging to the 19th-century philanthropist Countess Manduca. You see women in ankle-length ġonnejja carrying wicker baskets of ġbejniet down what is now Triq il-Kbira but was then simply “ir-triq tal-ħofor” (the potholed street) because British service vehicles en route to the 1943 Sicily invasion had chewed up the surface. Elderly visitors nod, smile, occasionally correct the captions – communal memory in real time.

Culturally, the photographs explode two persistent myths. First, that pre-war Maltese villages were monochrome places. Hand-coloured postcards by itinerant Sicilian studio photographer Salvatore Lorenzo show Siġġiewi’s feast banners in riotous crimson and emerald, proving villagers were unafraid of colour long before Technicolor. Second, that rural Malta was socially static. A 1922 shot documents a girls’ football match on the feast square, organised by the Society of Christian Doctrine (M.U.S.E.U.M.) to raise funds for tuberculosis sufferers – evidence that female sport and civic activism pre-date the island’s 1947 suffrage law.

Perhaps the most poignant section is devoted to “il-ħmira tal-blat” – the stone quarry that for 400 years fed Siġġiewi’s economy and whose abandoned galleries now lie beneath the new American University of Malta campus. Side-by-side images show 1930s quarrymen balanced on rudimentary wooden scaffolds, shirts translucent with dust, and the same lunar hollow in 2023, water-filled and fenced off, a hazard-turned-lake. The visual rhyme is unmistakable: yesterday’s sweat underwrites today’s skyline.

Local mayor Dominic Grech told Hot Malta the council will use the archive to apply for EU LEADER funds, creating an open-air photo trail along Siġġiewi’s heritage route. “Tourism is shifting from generic harbour views to authentic village cores,” Grech said. “These images are our competitive edge – nobody can photocopy our nonna’s doorstep.” Already, Airbnb hosts report bookings from returning emigrants who want to stand on the exact spot where their 1950s christening photo was taken, now holding a smartphone instead of a gas-powered Kodak.

School uptake has been equally enthusiastic. Teacher Ramona Attard has turned the collection into a cross-curricular module: students recreate period tableaux, calculate inflation on 1938 grocery lists visible in shop windows, and interview relatives who appear in the frames. “It’s the first time my Year 9s asked if homework could be longer,” Attard laughs.

As the closing hymn of the exhibition’s opening night faded – a crackling 1959 recording of the village banda playing ‘Marċ ta’ Siġġiewi’ – visitors stepped back onto the street blinking against the orange glow of LED streetlights. The contrast was jarring, but also comforting: the village may have swapped donkey hooves for diesel engines, yet its limestone bones remain reassuringly familiar. In an age when Maltese localities risk becoming architectural palimpsests, Siġġiewi’s old photographs are more than nostalgia; they are a permission slip to evolve without forgetting. Hold the image, and the place holds you back.