Malta’s Artists Demand Seat at Vision 2050 Table: ‘Culture Is GDP, Not Garnish’

Culture at the Crossroads: Why Malta’s Creative Heart Must Beat Louder in Vision 2050

Valletta’s Republic Street on a Friday night hums with more than café chatter and clinking wine glasses. Inside the old Knights’ granaries, a techno producer from Gżira is remixing ġħana folk samples for a Berlin label; upstairs, a 23-year-old game-design graduate from MCAST is storyboarding a Maltese-language RPG set in 1348, the year the plague first hit the islands. These are not side-hustles or cute heritage footnotes—they are the living proof that culture is Malta’s quietest, fastest-growing export. Yet when government officials unveil slides of Vision 2050—the strategic roadmap meant to carry the country beyond tourism, iGaming and passport sales—there is barely a bullet point for music, art, design or film. The Malta Entertainment Industry and Arts Association (MEIA) has had enough.

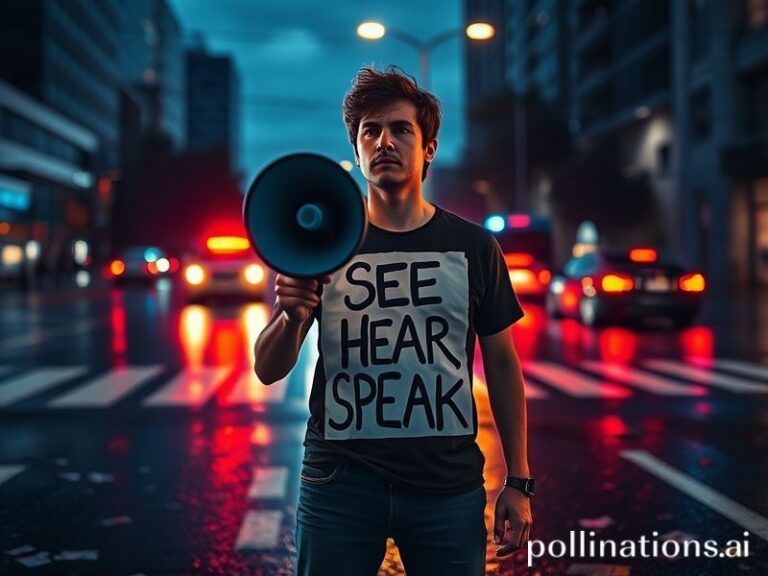

“Vision 2050 talks about AI, blockchain and carbon neutrality, but culture is still framed as a garnish,” MEIA president Howard Keith Debono told Hot Malta after an emergency meeting with arts stakeholders in Floriana last week. “We’re asking for culture to be embedded—hard-wired—into every pillar: education, foreign investment, even health.”

The numbers back him up. According to a 2023 study by the Central Bank of Malta, the cultural and creative sectors already contribute 4.2 % of GDP—larger than the fisheries sector and roughly equal to aviation services. More importantly, the jobs are sticky: 68 % of creative employees are Maltese nationals under 35, a demographic that traditional industries struggle to retain. “Every euro we put into a rehearsal room or a film rebate returns €1.80 in VAT alone,” Debono says. “That multiplier beats luxury condos.”

Walk through Sliema’s traffic-jammed streets and the contradiction is visible. Shuttered retail outlets are being converted into €7,000-a-month short-let flats, while artists who once rented upper-floor studios are pushed to Bormla or Marsa, where landlords still accept barter—stage lighting for three months’ rent. “We’re not asking for hand-outs,” says drag performer and LGBTQ+ activist Charlie Cauchi, who recently crowdfunded Malta’s first bilingual queer cabaret. “We’re asking for policy that treats space, bandwidth and copyright as infrastructure, just like roads and drainage.”

The urgency is geopolitical. With Saudi Arabia, Greece and even Cyprus ramping up film rebate schemes, Malta’s once-coveted 40 % cash rebate is losing shine. Productions that flocked to Fort St Elmo for Game of Thrones are now eyeing new Mediterranean sound-stages with better fibre-optic links. “If we don’t double down on post-production facilities and crew training, we’ll be a backlot for wedding videos,” warned film producer Rebecca Cremona (Simshar, 2014) at a Valletta Film Festival panel.

Community impact goes deeper than economics. In Gozo, the Nadur carnival—once dismissed as a boozy street party—now commissions local animators to create augmented-reality masks, luring winter visitors and filling farmhouses in February, traditionally a dead month. In Birżebbuġa, teenagers enrolled in the brass band club are 40 % less likely to drop out of school, a University of Malta youth study found. “Culture is the only sector that turns GDP into glue,” says sociologist Dr Maria Brown. “It keeps kids rooted, grandparents relevant, and tourists returning to the same bar to hear the same guitarist—something no casino loyalty card can replicate.”

MEIA’s proposal to Vision 2050 is blunt: ring-fence 1 % of every infrastructure contract for public art; create a “Night-Time Economy” mayor with powers over licensing and noise; fast-track artist visas for non-EU creatives willing to mentor locals; and designate 10,000 m² of vacant public buildings as zero-rent cultural incubators by 2026. “We’re not dreaming,” Debono insists. “We’re calculating.”

The political wind may be shifting. Culture Minister Owen Bonnici told parliament this month that a draft “Creative Industries Act” will be published before summer recess, promising tax credits for record labels and fashion start-ups. But artists remember past white papers that gathered dust next to abandoned opera house plans.

Meanwhile, outside the MEIA meeting, a teenager in a leather jacket is pasting up a poster for a punk gig in a Ħamrun garage. It’s cheap, it’s loud, and it won’t wait for Vision 2050. If Malta’s policymakers don’t carve out space, someone else will—and the islands’ greatest sustainable asset will once again be exported on the cheap, leaving only hangovers and empty wine bottles where a future could have grown.