Gozo’s Soul on Parade: Inside Victoria’s Explosive Feast of Our Lady of Divine Grace

Feast of Our Lady of Divine Grace fills Victoria with incense, brass and Gozitan pride

By Antoine Zammit

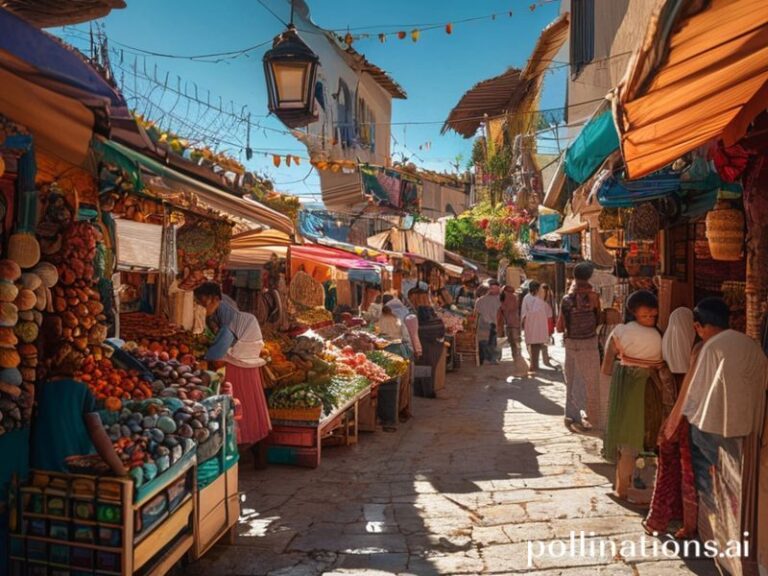

VICTORIA, GOZO – The narrow flag-strewn streets of Ir-Rabat echoed with drumrolls and hymn-singing long before the sun climbed over the Citadel on Sunday, as thousands converged for the Feast of Our Lady of Divine Grace. By 08:30, the statue of il-Madonna tal-Grazzja—her porcelain face gleaming beneath a gold-leaf cloak—was already swaying out of the 400-year-old church that carries her name, greeted by a volley of petards and the first brass notes of the local banda.

For Gozitans, the feast is less a calendar footnote than an annual heartbeat. “We don’t just honour the Madonna, we re-introduce ourselves to her,” said 82-year-old Karmenu Portelli, who has carried the processional cord for six decades. “My knees object, but she never does.” Portelli’s sentiment is shared by farmers from Xewkija, students from the sixth form, and British retirees who have swapped Surrey for San Lawrenz—all pressing shoulder-to-shoulder behind the statue as it inched toward Republic Street.

The cult of tal-Grazzja dates back to 1620, when a small chapel outside the walls was the only place of worship spared during a plague outbreak. Locals credited the Virgin’s “divine grace,” and the devotion stuck. Today the chapel has morphed into a baroque parish church, but the story is retold every year from the same stone pulpit, its limestone still scarred by 17th-century musket balls—an audible gasp rises from first-time visitors when the re-enactor smashes a clay pot symbolising the shattered epidemic.

Economically, the one-day feast punches above its 24-hour weight. Hotel occupancy in Victoria jumped to 96 % this weekend, according to Gozo Tourism Association figures released Sunday night. Restaurant owners along Triq ir-Repubblika reported two sittings for lunch and three for dinner; one chef joked he had “more covers than the Bible.” Even pop-up kiosks selling mqaret and imqaret (the sweet, date-filled pastry) sold out by 14:00, with teenager Maya Vella pocketing €400 “just for folding dough and smiling.”

Yet the feast’s real currency is social. After two years of pared-down processions due to COVID, the 2024 edition felt like a communal exhalation. The parish commissioned 25 new damask banners sewn by unemployed single mothers enrolled in a government skills scheme—each stitch literally weaving livelihoods into liturgy. Meanwhile, the village youth section mounted a TikTok campaign (#Grazzja2024) that drew 18,000 views in 48 hours, pairing drone shots of the Citella with techno remixes of the Litany of Loreto. “We refuse to be a museum piece,” said 19-year-old banda flautist Davide Azzopardi. “Tradition survives when it dances with the present.”

Environmental concerns, however, shadow the fireworks. NGO Graffitti staged a silent vigil at 07:00, handing out cardboard masks of the Madonna painted in eco-green. “We love the feast, but we want silent fireworks and biodegradable confetti,” spokesperson Sasha Cini said. Her plea gained traction: the parish priest announced from the balcony that next year’s budget will earmark €5,000 for low-smoke pyrotechnics, prompting applause even from pyromaniac teens.

By 19:00, the statue completed its final lap, returning to the church beneath a canopy of 1,000 tealights held by children whose grandparents once carried candles made of lard and cotton. The banda struck up the hymn “Grazzja t’Alla,” its final note dissolving into spontaneous cheers. Then, as quickly as it began, the square emptied—petard sticks swept aside, plastic cups binned, balconies stripped of damask. Victoria slipped back into its weekday hush, but the scent of incense lingered like a promise: tal-Grazzja will return, and with her, an entire island’s sense of itself.

Conclusion

In a country that stages more than 80 village feasts a year, the Feast of Our Lady of Divine Grace proves that size is no measure of soul. What Victoria lacks in population—barely 7,000 residents—it multiplies in resonance, turning centuries-old gratitude into 21st-century community glue. Whether you crossed the channel for faith, food or Facebook-worthy footage, you left reminded that Gozo’s greatest export isn’t cheese or lace, but the unwavering conviction that heaven and earth can share the same narrow street, if only for a day.