London on Lockdown: 1,000 Police Contain Far-Right Chaos—Maltese Expats Tell Their Story

1,000 Police Lock Down London As Far-Right And Anti-Racist Crowds Clash—What It Means For Maltese Living In The Capital

By Hot Malta Correspondent

Valletta time: 16:45. While Sliema ferries bob gently in the afternoon sun, WhatsApp groups linking Maltese students in Camden and nurses in Hammersmith are pinging non-stop: “Avoid the Strand, tubes closed.” “Stay indoors, sirens everywhere.”

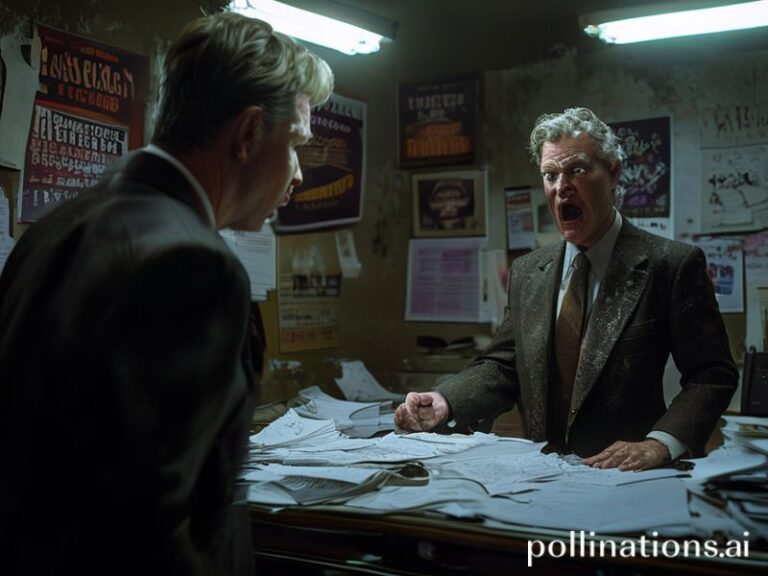

On Saturday, the Metropolitan Police threw a ring of steel around Whitehall, deploying almost 1,000 officers—Britain’s largest single-day mobilisation since the 2011 riots—after intelligence showed far-right activists and anti-racism counter-protesters heading for the same patch of Westminster.

For the 30,000-strong Maltese community spread from South Kensington to Wembley, the tension felt eerily familiar. “We’ve seen heated demos before, but this smelled different,” says Maria Camilleri, 26, a University College London postgraduate who left Żebbuġ three years ago. “Police vans racing down Oxford Street reminded me of the 2019 Valletta protests, only on steroids.”

The trigger? A social-media call by the far-right group “Football Lads Alliance” to “protect the Cenotaph” from Black Lives Matter supporters. Never mind that BLM had cancelled its rally hours earlier; viral screenshots kept the rumour mill churning. By lunchtime, skinhead groups from Luton and Portsmouth were drinking in pub doorways, while Stand Up To Racism coaches arrived from Manchester and Cardiff.

Maltese flags—usually fluttering outside Earls Court cafés during Eurovision season—were conspicuously absent. “We kept our heads down,” explains Fr Joe Borg, chaplain of the Maltese Catholic Mission in London. “Our parishioners drive buses and work in NHS wards. The last thing they need is to be caught between shield charges.”

By 14:00, police had sealed every bridge south of the Thames. Helicopters thudded overhead, mimicking the sound of Malta’s 1981 election riots still etched in older migrants’ memories. Shopkeepers on the Strand pulled shutters halfway, the way Gozitan boutiques do when the feast procession route turns rowdy.

The Met imposed rare Section 60 stop-and-search powers, later extending them until dawn. Officers seized knives, smoke grenades and at least one knuckle-duster. Thirty-three arrests were made for affray, racially aggravated assault and possession of offensive weapons—figures that dwarf Malta’s entire annual protest tally.

Yet the cultural resonance goes beyond crime stats. Britain’s debate over monuments—slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, Winston Churchill’s boarded-up bust in Parliament Square—mirrors Malta’s own soul-searching about colonial heritage. “When I saw Churchill boxed in plywood, I thought of Knights’ statues being spray-painted in Valletta last June,” notes historian Dr Grazia Montebello, who teaches at Queen Mary University. “Both islands are negotiating which memories deserve pride of place.”

Community impact is already tangible. Maltese chef Daniela Pace, co-owner of “Café de Malte” in Covent Garden, cancelled her Saturday seafood delivery. “Police cordons meant suppliers couldn’t cross Waterloo Bridge. We lost €1,200 in rabbit-fenek orders booked by Maltese expats craving home flavour.” She fears insurers will hike premiums if unrest becomes routine.

Back in Malta, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs told Hot Malta it is monitoring the situation via its High Commission. No Maltese citizens have requested consular assistance so far, but emergency travel documents are on standby.

Meanwhile, grassroots solidarity sprouted. L-Isle of Malta Society, a London diaspora group, opened its Holborn clubrooms to anyone stranded by closed Tube lines. Volunteers handed out Kinnie and pastizzi, turning a potential flashpoint into an impromptu Maltese tea party. “Food calms nerves better than tear gas,” laughs volunteer Rene’ Micallef, clutching a tray of still-warm imqaret.

Sunday morning, Westminster cleaners swept broken bottles as joggers reclaimed the pavements. Yet the psychological aftertaste lingers. “Malta is ten flights away, but WhatsNet shrinks the ocean,” says student Camilleri. “When London burns, our group chats feel the heat.”

Whether the far-right will regroup next weekend remains uncertain. What is clear is that Maltese Londoners—like so many migrant communities—have added a new item to their survival toolkit: group geo-location sharing and a ready stash of pastizzi, just in case the capital flares again.