From Sliema to Serowe: How Malta’s €8.3 Million Lab-Grown Diamond Habit Is Quietly Devastating Southern Africa

Lab-Grown Diamonds Sparkle in Malta While Southern Africa Loses Its Lustre

*How Sliema’s jewellery quarter is unwittingly fuelling a crisis 7,000 km away*

On a humid July afternoon, the plate-glass windows of Tower Road sparkle like a pirate’s chest. Inside, a young Maltese couple hover over a white-gold ring set with what looks like a 1.5-carat flawless diamond. The price tag—€1,200, a third of its mined equivalent—makes them grin. Neither notices the small print: “Laboratory-grown, origin: China.”

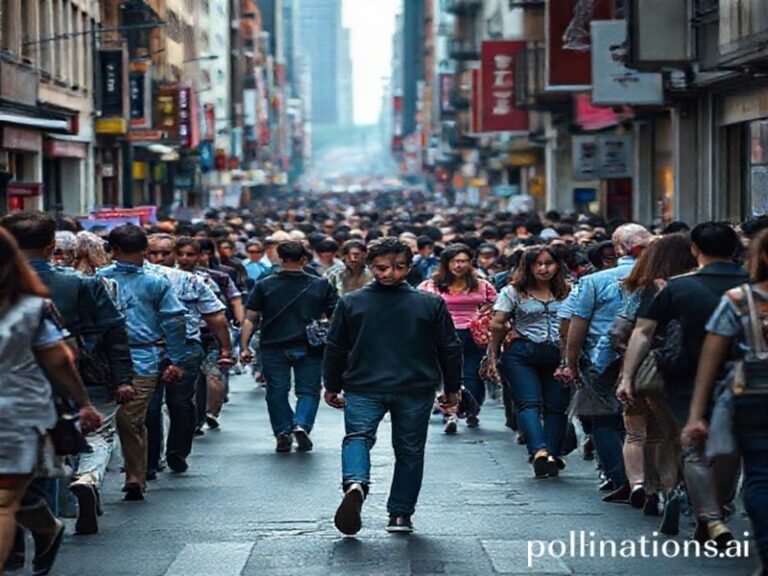

Three weeks earlier, 7,000 km south, 34-year-old Kabelo Mokoena descended into Botswana’s Jwaneng mine for the last time. The shaft, once the richest diamond artery on Earth, is being “mothballed” until 2025. De Beers, which has shipped gems from here since 1972, cites “market headwinds” – a polite phrase for the tsunami of lab-grown stones flooding jewellery counters from Sliema to Shanghai.

Malta, statistically, is a rounding error in the $80 billion global diamond trade. Yet the island’s 28 licensed jewellers sold an estimated €8.3 million in engagement rings last year, 42 % of them set with lab-grown diamonds, up from 9 % in 2019. The shift is visible in Valletta’s Republic Street, where billboards promise “Ethical Bling, Zero Guilt” above outlets that once traded in Kimberley-certified African stones.

But the guilt has merely been exported. In southern Africa, diamonds are not just luxury goods; they are sovereign glue. Botswana’s national budget is 30 % funded by diamond royalties. When prices collapse, nurses in Francistown are retrenched, and HIV clinics in Maun run short of antiretrovirals. Namibia’s diamond-diving fleet has already laid off 1,200 sea-going sorters; their families now queue at Windhoek food banks. Angola, still recovering from 27 years of civil war, had pegged its post-conflict reconstruction on diamond taxes; the IMF quietly warns of “fiscal distress” by 2026.

Back in Malta, the ethical pitch is seductive. “No child labour, no warlords, no environmental scarring,” insists Julianne Camilleri, manager of EcoGems in Paceville, whose Instagram reels show pristine silicon reactors instead of scarred earth. What the reels omit is energy: most lab growers rely on coal-fired grids in China and India, generating up to 511 kg of CO₂ per polished carat—three times a Botswana mine powered by Botswana’s solar-thermal plants.

Cultural irony abounds. Maltese fiancés still kneel on the limestone steps of the Mdina cathedral, reciting vows sealed with a ring whose carbon may have been cooked in a Shenzhen reactor. Meanwhile, Setswana initiation songs that once celebrated “the stone that feeds the clan” fall silent. Last month, the village of Serowe—birthplace of Botswana’s first president—cancelled its annual diamond festival; the council could not afford the €9,000 licence for the kgotla (community square).

The human pinch is personal. Paulina Tshuma, a 52-year-old widow from Zimbabwe’s Marange fields, used to earn €180 a month hand-sorting diamonds. She now sells frozen chickens on the roadside near Mutare, earning €2 on a good day. “The white coats in Europe say their stones are clean,” she told Hot Malta via WhatsApp voice note. “But my children’s plates are empty.”

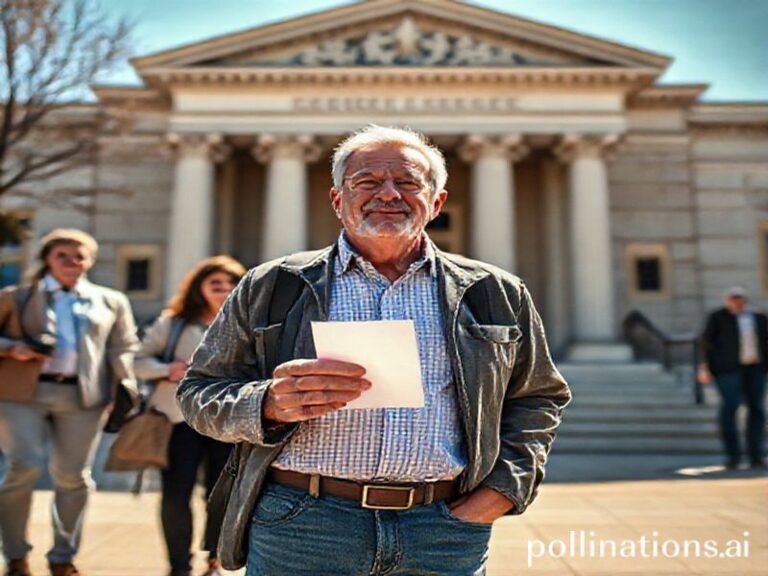

Malta’s Consumer Affairs Authority has no rules compelling jewellers to separate lab-grown from mined stones beyond microscopic laser inscriptions. A draft EU directive, debated in Brussels next March, may oblige sellers to state country-of-origin for both categories. Until then, Maltese shoppers can legally walk out with a “Made in China” diamond whose carbon footprint is stamped “conflict-free” while African miners watch their economy evaporate.

What can an island micro-state do? More than one thinks. Maltese jewellers pioneered the “Filigree for the Future” campaign, reviving antique silverwork to reduce gold imports. A similar scheme could promote responsibly mined African stones, perhaps marketed through a “FairCarat” label backed by Malta’s influential Catholic development NGO, Missio. Already, one Gozo-based designer, Maria Farrugia, sources diamonds from Namibia’s land-based Namdeb mine, which reinvests 55 % of profits into community trusts. Her €3,000 rings fly off the shelves of her Xlendi studio—proof that conscience can sell.

Until such initiatives scale, the sparkle in Sliema comes at the cost of darkness in southern Africa. Every €1,000 saved on a lab-grown solitaire equals roughly two months of public-sector wages lost in Botswana’s health ministry. The true price of a diamond is no longer measured in carats, but in classrooms that will not be built, nurses who will not be hired, and songs that will not be sung.

As the Maltese couple leave the shop, the ring catches the Mediterranean sun, scattering tiny rainbows across the promenade. They are beautiful, those rainbows. They are also the spectral remnants of someone else’s vanished future.