Malta’s Microscopic Edge: How Tiny Textures Are Saving Millions & Creating Jobs

Friction to Function: How Malta’s Engineers Turn Texture into Treasure

Valletta’s 16th-century bastions are smooth to the eye but surprisingly grippy under a rubber-soled shoe. That silent grip—stone micro-ridges catching polymer peaks—is the same physics now guiding Maltese start-ups as they 3-D-print shark-skin textures onto yacht propellers and hospital door-handles. From Lascaris War Rooms to the new Bormla pedestrian lift, texture is Malta’s unsung engineer, deciding what slips, sticks or survives our salt-laden winds.

Walk into the University of Malta’s Engineering Labs at 08:00 and you’ll find Prof. Josephine Briffa’s team rubbing seashells against sandstone. “We’re mapping roughness values,” she explains, holding a €40,000 laser profilometer that looks like a supermarket scanner. “Malta’s limestone ranges from 0.8 to 4.3 micrometres Ra—data we feed into finite-element models for heritage clamps.” In plain English: knowing exactly how rough a piece of Mdina bastion is lets conservators design stainless-steel brackets that grip without cracking the stone. The €1.2 million EU-funded project has already saved 17 metres of wall at Fort St. Elmo, cutting future repair bills by an estimated 35 %.

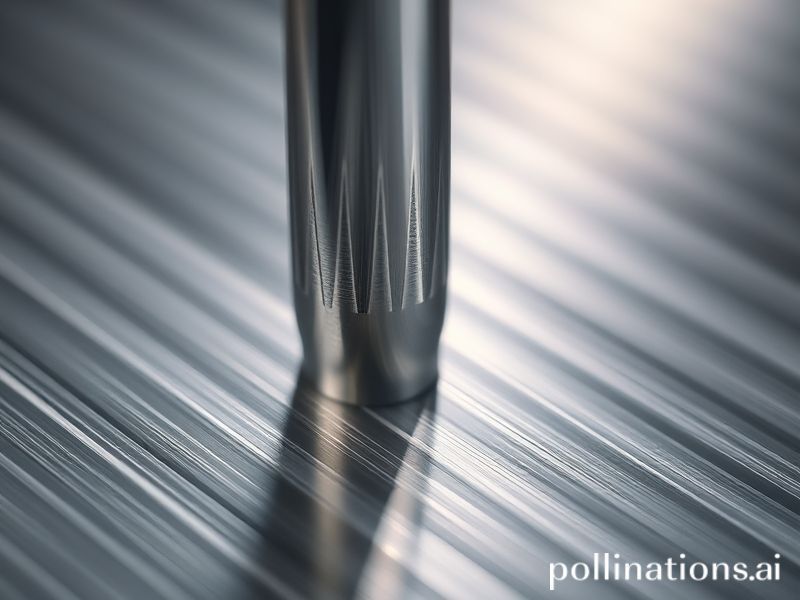

Across the water in Malta Enterprise’s smart-manufacturing hub, start-up TractionLab is borrowing texture tricks from tuna. “We scan the scale ridges of fast-swimming local fish, then laser-etch those grooves onto propeller hubs,” says CEO Matthew Xerri. The biomimetic surface reduces drag by 4 %—tiny until you multiply it across a 40 m super-yacht burning 400 litres an hour. With Malta’s super-yacht sector worth €120 million annually, charter owners are queuing up. The spin-off: 12 new jobs for machinists in Paola, plus a summer internship that sends MCAST students out on fishing boats with handheld 3-D scanners.

Texture even shapes public health. Mater Dei Hospital reported a 22 % drop in door-handle bacterial count after swapping glossy stainless for copper alloy etched with a microscopic cross-hatch. “Peaks and valleys rupture cell walls,” explains consultant microbiologist Dr. Elena Saliba. The €70,000 retrofit—funded by Bank of Malta’s community scheme—has inspired Gozo General to follow suit, and sparked a side-business: Qormi-based MetalloPrint now exports antimicrobial lift buttons to Romania.

Culturally, Maltese artisans have always trusted touch. The knapped flint of megalithic temples, the ribbled finish of traditional xorok fishing nets, the raised gilding on a Good Friday statue—all celebrate surface. “Texture is memory,” says craftsman Jesmond Vella, hand-sanding a limestone replica of a Mnajdra spiral. “You feel it before you see it.” Modern engineers are simply quantifying what stone-carvers knew by callus: roughness equals grip, grip equals longevity.

For commuters, the payoff is literal grip. Transport Malta’s new bus fleet uses shot-blasted aluminium flooring that keeps traction even when drenched in sea spray. Fall incidents are down 18 % since 2022, saving an estimated €50,000 in compensation claims—money diverted instead to planting 200 carob trees along the Marsa junction.

Yet the biggest winner may be Malta’s youth. A joint Junior Achievement-MCAST programme challenges secondary-school teams to texture-design a product in 24 hours. Last year’s winners—Girls’ Secondary Żejtun—created a knurled cap that lets arthritic hands open water bottles. Their prize: a €5,000 prototype grant and mentorship from TractionLab. “We’re teaching teenagers that surface finish isn’t cosmetic—it’s economic,” says educator Claudia Farrugia.

From temple builders to 3-D printers, Malta keeps proving that the difference between a sliding stone and a standing civilization is a few micrometres of intentional roughness. In a country where every square metre has been contested, carved, bombarded and rebuilt, texture is not just engineering—it’s identity you can feel under your fingertips.