Malta’s Ink Rebellion: How Letters to the Editor Still Shake the Islands in 2025

Letters to the editor – September 15, 2025

By Hot Malta Staff

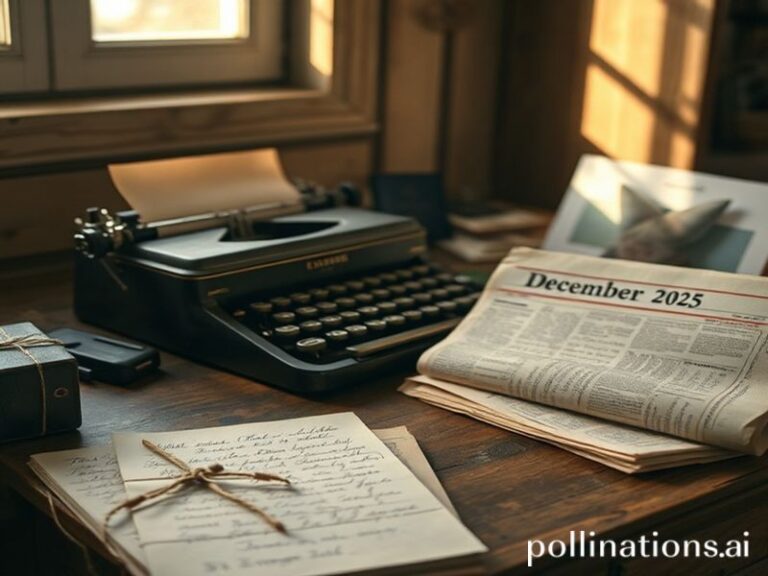

Valletta’s 17th-century printing press at the National Library is humming again, but this time it’s not stamping out parish notices for knights. Every Monday morning volunteers feed a stack of A4 sheets into the antique machine and produce 2,000 copies of “Ittra Maltija”, the only stand-alone letters page still circulating on the islands. The 15 September edition hit doorsteps at dawn, and by 9 a.m. The kiosk outside the Law Courts had already sold out—twice.

In an age when Facebook threads detonate faster than petards at a village festa, the persistence of ink-on-paper letters feels almost archaeological. Yet editors at the Times of Malta, Malta Today, and even the church-owned Leħen Parroċċa all report record postbags. “We received 438 letters last week,” says Claire Bonello, opinion editor at the Times. “That’s triple the volume of five years ago.” The phenomenon is being studied by sociologists at the University of Malta, who call it “reactive nostalgia”: a collective craving for slower, traceable debate after years of doom-scrolling.

What makes today’s batch unique is how hyper-local the grievances are. One writer from Żebbuġ complains that the new pedestrian zone is funneling traffic straight into her nan’s olive grove. Another, signing off as “Tarxien Taxpayer”, demands to know why the council spent €50,000 on a fibreglass temple replica “when the real ones are still shedding limestone flakes like dandruff”. The letters are peppered with Maltese idioms—“qisu qahba f’konfessiona” (“like a prostitute in confession”)—that lose their chilli when translated online.

Cultural anthropologist Dr. Katya Micallef argues the page functions as a 21st-century kantina. “In village bars men used to solve the world’s problems over a Cisk. Now the bar is closed for renovations, so the argument moves to newsprint.” She points to recurring tropes: the cost of tomatoes, the decibel level of brass bands, the correct way to stuff a rabbit. “These aren’t trivial. They’re identity markers.”

The impact can be immediate. Last month a single letter about raw sewage bubbling onto Għar Lapsi’s pebble beach forced the tourism minister to schedule an emergency clean-up before the weekend rush. Photographs of volunteers in rubber gloves went viral, but the spark was 220 words printed beside a crossword. “We’ve become the island’s notice board,” jokes Ramon Fsadni, who curates “Ittra Maltija”. “But one with a circulation audited by ABC.”

Not everyone applauds. Earlier this summer a Birkirkara resident penned a sarcastic note mocking “lazy Gozitans” who “cross the channel to steal our overtime”. The Gozo ferry was briefly flash-mobbed by islanders waving the page like a battle flag. “Satire can backfire,” admits Fsadni, “but the fact that people care enough to protest shows the medium still punches.”

Gender balance remains elusive; only 27 % of published letters come from women. A new initiative—“Nitkellmu Aħna” (“We Speak Up”)—encourages female contributors by offering creche vouchers for every printed letter. Early uptake is promising: last week’s star piece came from 19-year-old Sliema student Leah Cauchi, who skewered the “boys-club mentality” at junior football clubs after her little sister was told girls belong on the sidelines. The Malta FA has since invited her to consult on its new equality charter.

As storm clouds gather over the Grand Harbour, today’s letters are being clipped to fridge doors in flats from Marsa to Mellieħa. Some will be folded into wallets, others read aloud to elderly relatives whose eyesight no longer tolerates screens. In a country where 92 % of the population owns a smartphone, the printed letter survives because it is slow, shareable, and stubbornly Maltese.

Conclusion

Whether railing against band club subsidies or defending the spelling of “ħobż biż-żejt”, the letters page remains Malta’s most democratic soapbox. It turns private irritation into public dialogue, and occasionally into policy. So the next time you hear the thud of the newspaper against the doorstep, pause before you swipe to the sports section. Somewhere between the parish lottery results and the obituaries, a neighbour is handing you the mic. Use it wisely—it might just rebuild a beach, a football league, or even a village identity.