Malta’s Wardrobe Awakening: How Ethical Fashion Is Stitching Communities Together

Has your clothing been produced ethically?

On a humid Saturday morning in Valletta, while tourists queue for pastizzi, 23-year-old student Leanne Saliba is hunting for a different kind of souvenir. She flips the collar of a linen blouse inside-out, scans the care label with her phone, and frowns. “Made in Bangladesh – but no certification,” she sighs. “I’ve read too many horror stories to buy blind.”

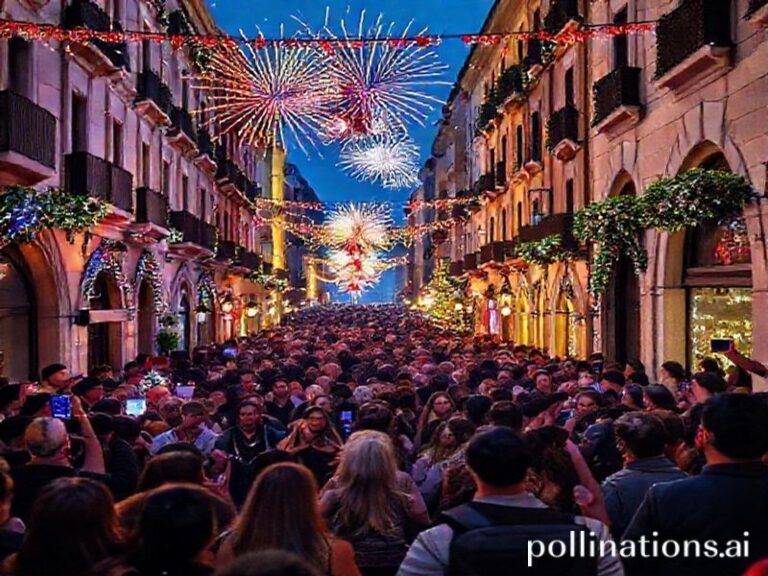

Saliba is part of a growing cohort of Maltese shoppers asking the uncomfortable question: who really pays for our €4 T-shirts? The island may be small, yet its fashion footprint stretches from the cotton fields of Gujarat to the sweatshops of Dhaka. Every year Malta imports roughly 18 million garments – nearly 36 pieces for every man, woman and child. Until recently, few questioned the journey behind each item. Now, Facebook groups like “Malta Ethical Fashion Swap” (8,400 members) and University workshops on “slow style” are turning conscience into a campus trend.

The shift is personal for Sarah Galea, a Birkirkara secondary-school teacher who lost a cousin in the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse. “After the tragedy I emptied my wardrobe,” she recalls. “Anything without transparent sourcing went to charity.” Galea channelled her grief into action, founding SewGood Malta, a volunteer collective that repairs and upcycles clothes for refugee families. On any given Thursday evening, her living room hums with sewing machines and multilingual chatter as Iraqi tailors teach Maltese retirees darning techniques. Last year the group saved 1.2 tonnes of fabric from landfill – the weight of a traditional luzzu boat.

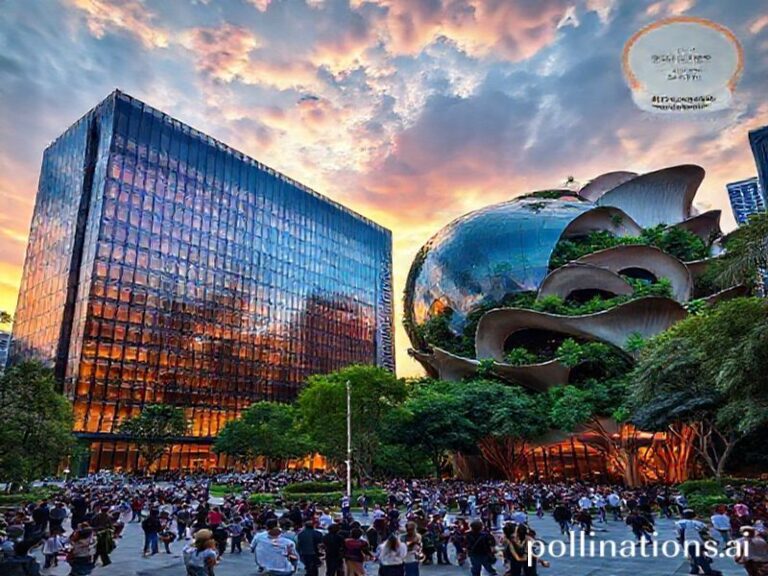

Ethical fashion is also reviving almost-forgotten Maltese crafts. Take the qoffa weave, once used for fisherman baskets. Designer Luke Buttigieg has re-imagined the pattern in recycled ocean plastic, creating unisex tote bags stitched by Gozitan artisans. “Our grandfathers repaired nets; we’re repairing the planet,” he jokes at his Sliema pop-up, where each bag comes with a QR code tracing the plastic’s journey from Mellieħa beach to finished product. The price – €65 – prompts the occasional whistle, but Buttigieg’s summer run sold out in ten days, proving consumers will pay for provenance.

Still, sustainable shopping on the island faces structural headwinds. Malta’s only commercial recycling plant for textiles closed in 2021 after fire damage. With repair cafés limited and import taxes favouring fast-fashion conglomerates, ethical choices often feel elitist. “I can’t afford a €90 organic-cotton dress,” argues Kim Vella, a cleaner and mother of two from Żabbar. “My kids grow every three months.” Vella’s workaround is the Żejtun open-air market at dawn: she buys second-hand bundles for €5, washes, mends and resells on Facebook Marketplace, funding school uniforms in the process. Her side-hustle earns roughly €200 a month – small change that makes a big difference.

Retailers are beginning to respond. International brand Mango has introduced a “Committed” line in its Bay Street outlet, while local favourite Charles & Ron now sources linen from an EU-certified mill in Portugal and publishes factory wages online. Even the government is dipping a toe: last April, Parliamentary Secretary Rebecca Buttigig launched a €200,000 grant for start-ups that turn waste fabric into new products. Applicants must prove social impact, such as employing migrants or single mothers. The first recipient, Nanna’s Remnants, hires elderly seamstresses to make scrunchies from hotel linens diverted from landfill; the finished accessories are sold at Malta International Airport, giving travellers a literal piece of the island’s circular economy.

Yet the most powerful change may be cultural. During this month’s village festa of St Gregory in Sliema, organisers swapped imported polyester banners for hand-painted cloth panels that will be reused annually. The parish priest, Fr Anton D’Amato, framed the move in his homily: “Caring for garment workers thousands of miles away is an act of caritas – our faith in action.” Worshippers applauded; one even pinned a paper straw to her lace faldetta in solidarity.

So, has your clothing been produced ethically? In Malta, the answer increasingly shapes not just wardrobes but identity. Choosing a recycled-cotton Gozitan tee over a €3 import is becoming as much a statement as ordering a local ġbejna instead of imported cheddar. The island’s size, once a limitation, is now an advantage: supply chains are short, stories travel fast, and every purchase ripples through a community bound by tighter degrees of separation than the stitches on a shirt. As Sarah Galea puts it while folding a pile of upcycled baby-grows, “Fast fashion exploits someone we’ll never meet. Slow fashion empowers someone we might bump into at the grocer tomorrow.” And in Malta, tomorrow is always just around the corner.