Watch: Malta’s Blue Lagoon Reinvented—First Look at the €14M Eco-Revamp

Watch: How Blue Lagoon will look after rehabilitation

By Hot Malta Staff

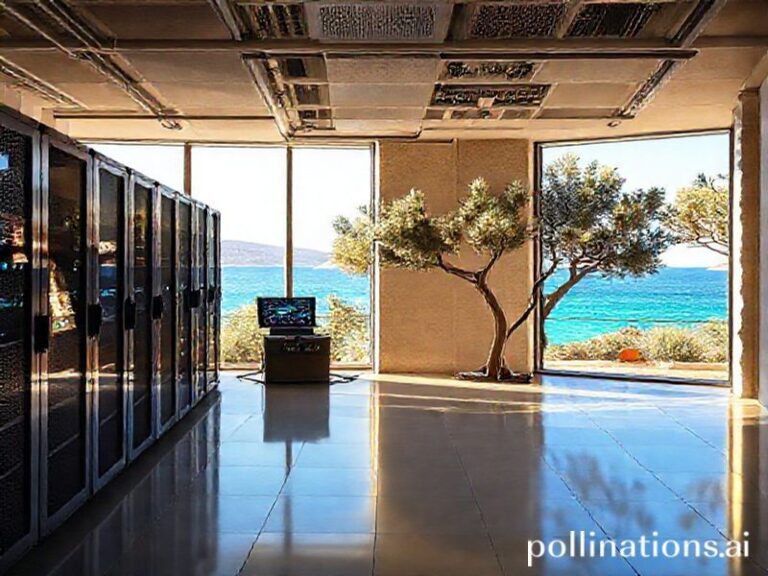

COMINO – The first drone footage dropped at 07:02 this morning and within minutes every family WhatsApp group from Siġġiewi to Xagħra was buzzing. In the 42-second clip the Blue Lagoon looks almost unrecognisable: the chrome-blue skin of water is still there, but the armada of plastic kayaks, selfie-stick vendors and thundering speedboats has vanished. In their place float twelve discreet, solar-powered pontoons modelled on the traditional Maltese dgħajsa, a wooden walkway that snakes around the reef without a single concrete footing, and, most radical of all, a daily cap of 1,500 visitors accessed by timed e-tickets.

“Finally, we’re giving the rock back its voice,” Environment Minister Miriam Dalli told Hot Malta as she watched the renderings on a tablet at the Comino police post. The €14 million EU-funded rehabilitation—unveiled ahead of next summer’s peak season—will reshape not just the island’s most Instagrammed cove but, officials hope, the entire conversation about carrying capacity in Malta’s €2.2 billion tourism economy.

From corsair haven to carnival

Comino’s 3.5 square kilometres have always punched above their weight. In the 16th century the Knights used the island as a quarantine station for plague ships; in the 1970s it doubled as a Bollywood set; by the 1990s it had become the poster child of low-cost Mediterranean hedonism. Locals old enough to remember pre-TikTok summers speak of anchoring on a Tuesday, frying lampuki on deck and not seeing another soul until Friday. “Now you’d swear you’re in Paceville if you closed your eyes,” says 68-year-old Marsaxlokk fisherman Ġużeppi “Peppu” Vella, who claims he avoids the channel “like tuna avoid plastic.”

The numbers back him up: in 2022 Transport Malta logged 4,200 boat movements on a single August day, while ERA estimates that 80% of litter collected on Comino beaches originates from visitor snack packs. The cacophony of engines has also pushed the island’s 30 breeding pairs of Yelkouan shearwaters to nest farther out on sheer cliffs, forcing bird-watchers to kayak into open water for a glimpse.

Designing silence

The rehabilitation masterplan, drawn up by Valletta-based architects Eleni & Vella together with Dutch eco-engineers Witteveen+Bos, borrows heavily from Malta’s limestone heritage. Low-lying rubble walls—identical to the ones farmers once built to divide Żebbuġ fields—will reroute foot traffic away from nesting sites. Shade is provided by canopies woven from bamboo grown in Għarb, not the usual aluminium parasols that end up in landfill. Even the new composting toilets are clad in the warm honey stone of Gozo, quarried sustainably from an abandoned Ta’ Kercem site.

But the biggest cultural shift is invisible: a geofenced app that turns every ticket into a “digital pledge.” Visitors unlock an augmented-reality tour narrated in Maltese and English; finish the 15-minute story and the app plants a seagrass seedling tracked in real time. Fail to show up for your slot and the €10 conservation levy is forfeited to a local farmers’ cooperative that tends the seedlings—an elegant loop that ties tourism directly to habitat restoration.

Community purse strings

Back in Gozo, hoteliers are cautiously optimistic. “We’re selling tranquillity now, not just tan lines,” says Maria Farrugia, who converted her family’s 19-room guesthouse in Xlendi into a shearwater-themed eco-lodge. Ferry operators, however, worry about revenue. “If the daily cap is 1,500, that’s half my August load,” complains Captain Joe Saliba, whose 120-seat catamaran does six runs a day. Government sweeteners—reduced VAT on hybrid engines and a €2 passenger rebate for off-peak sailings—are designed to soften the blow, but Saliba wants guarantees the cap won’t shrink further.

Labour unions are watching too. Some 450 seasonal deckhands, many from the south-east fishing village of Marsaskala, depend on the Blue Lagoon conveyor belt. ERA promises retraining as “marine custodians”—think snorkel guides and drone rangers—but salaries capped at minimum wage have raised eyebrows.

A lagoon for our children

Still, the mood on Comino this morning felt almost festive. A group of local divers surfaced shouting that they’d spotted a juvenile dusky grouper—once so overfished it was nicknamed “Nenu the myth.” Primary-school kids from Sannat were sketching the new pontoons, their teachers using the redesign to explain buoyancy and heritage in one breath. Even the police dog, a German shepherd called Kiko, seemed to wag his tail in approval as officers confiscated a crate of single-use water bottles.

Whether the renderings survive first contact with 30-degree August reality remains to be seen. But for a nation that has often sold its jewels to the highest bidder, the Blue Lagoon blueprint offers something rarer than turquoise water: a second chance to get the balance right.

As the drone footage ends, the camera tilts skyward, revealing the limestone cliffs glowing like burnt toast in the morning sun. A caption flashes: “Qatra qatra tagħmel ilmiera”—drop by drop, we fill the well. It’s an old Maltese proverb; today it feels like a promise.