Malta Says Goodbye to the Lion: CrediaBank Snaps Up HSBC Malta in €228m Discount Deal

CrediaBank’s €228m Knock-Down Deal: HSBC Malta Braces for a New Era

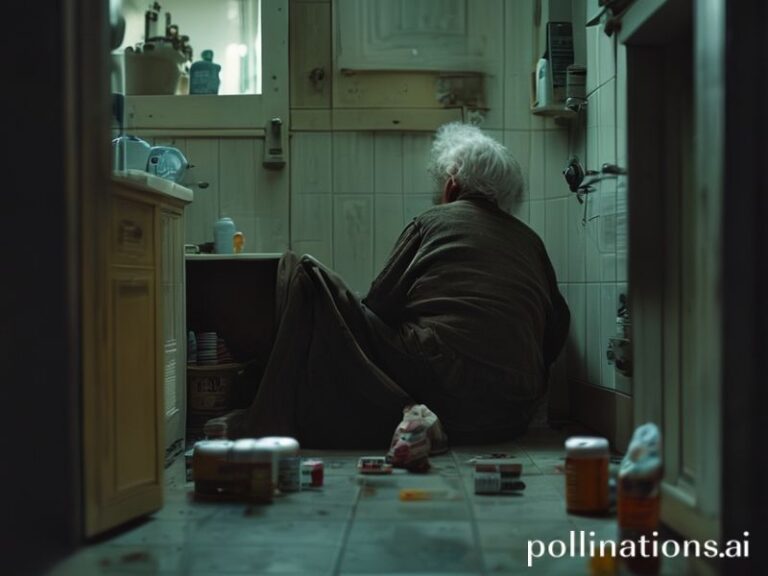

Valletta – When CrediaBank announced yesterday that it will swallow HSBC Malta for €228 million less than book value, the first reaction on the islands was not financial but emotional. “It’s like watching the last British bus leave the depot,” said 72-year-old Edward Zammit as he queued inside the 1960s marble-clad HSBC branch on Republic Street, clutching a passbook he’s held since his first pay packet at the Drydocks in 1971. “First they took the red phone boxes, now they’re taking the red hexagon.”

The discount—roughly 30 % off HSBC’s net asset value—immediately raised eyebrows in Castille Place and at the coffee tables of Café Cordina. But beyond the spreadsheets, the takeover marks the end of a 54-year chapter in which HSBC (formerly Mid-Med Bank) acted as Malta’s de-facto central banker, lender to dockyard workers, and sponsor of everything from the Malta Jazz Festival to the village festa fireworks in Żejtun.

CrediaBank, a 2018 start-up headquartered in Limassol with Bulgarian-Israeli capital, has promised to retain all 1,100 local jobs and keep the 29-branch network intact for at least three years. Yet scepticism runs deep. “We’ve heard ‘no redundancies’ before,” remarked Marceline Buhagiar, secretary of the Bank Employees’ Section of GWU. “Our members want guarantees written in Maltese law, not in press releases.”

Finance Minister Clyde Caruana hailed the deal as “a vote of confidence” in Malta’s post-grey-list economy, noting that CrediaBank has pledged to inject €400 million of fresh capital and expand SME lending. But Opposition spokesperson Jerome Caruana Cilia warned Parliament that the island is “trading a systemically important UK-regulated titan for an unlisted entity whose ultimate beneficial owners are shielded by Cypriot holding companies.”

For everyday savers, the cultural resonance is impossible to ignore. HSBC’s lion logo has guarded the façade of the former Mid-Med headquarters in Santa Venera since 1999; locals still call the roundabout “il-ljun” (the lion). Pensioner Rita Camilleri from Birkirkara admits she keeps €300 in a Christmas club account “just to walk past the lion every December”. She now wonders whether CrediaBank will replace it with “some plastic bull in EU blue”.

The timing is also politically sensitive. Malta is preparing to exit the FATF grey list this June, and regulators are wary of any upheaval that could spook correspondent banks. Central Bank governor Edward Scicluna sought to reassure, saying the takeover “passed preliminary fit-and-proper tests” and that depositor protection schemes remain unchanged. Still, some analysts fear the deal could accelerate de-risking by US banks already nervous about Maltese IBANs.

Small businesses, the backbone of the economy, are watching interest rates like hawks. HSBC currently controls 28 % of Malta’s SME loan book; CrediaBank says it will match existing pricing but hinted at tighter collateral requirements. “If they pull the plug on seasonal overdrafts, we’ll see a lot of beach kiosks and restaurant terraces closing next April,” warned Sandro Chetcuti, CEO of the Malta Chamber of SMEs.

In the gaming and crypto spheres, the reaction has been more upbeat. CrediaBank has made a name in Cyprus processing fintech payrolls and has applied for a Maltese VFA licence. Several iGaming CEOs told *Hot Malta* they welcome a challenger less “trigger-happy” than HSBC when freezing accounts flagged for Bitcoin purchases.

Yet for ordinary Maltese, the takeover feels like another layer of identity peeling away. HSBC’s cash-points once dispensed Maltese-lira notes adorned with Ġgantija temples; today’s euros feel generic enough without losing the familiar red-and-white interface. “My son has Revolut, my daughter uses BOV mobile, but I liked the queue where I could gossip in Maltese,” sighed 68-year-old Nenu from Sliema. “These foreigners won’t understand ‘mela’ and ‘u iva’.”

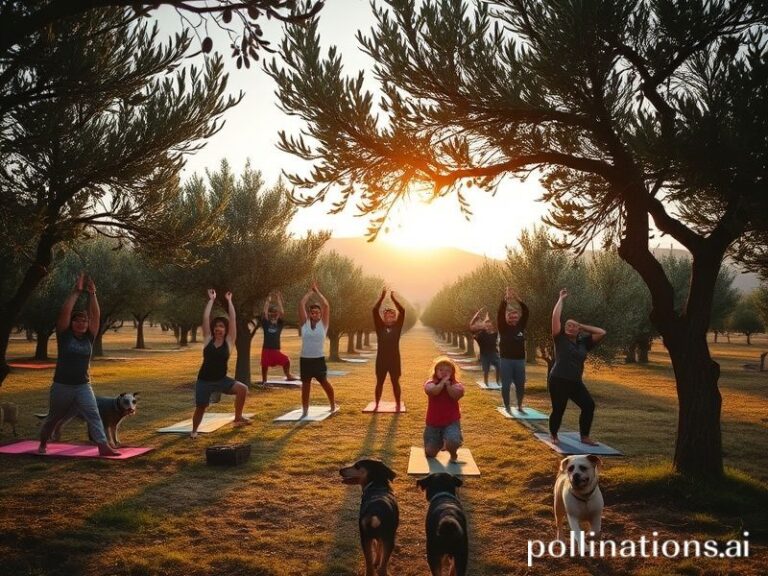

CrediaBank says it will launch a 12-month “listening tour” of village band clubs and parish centres—a savvy PR move in a country where trust is built over ħobż biż-żejt rather than Zoom calls. Whether Limassol bankers can master the art of kissing babies at festa processions remains to be seen.

What is certain is that by 2025 the lion will roar no more. In its place, a yet-unnamed predator from the eastern Mediterranean will prowl Malta’s financial savannah. For an island that spent centuries swapping Phoenician, Arab, Norman and British rulers, the lesson is clear: the flags change, but the limestone stays. The question now is whether CrediaBank will carve its initials alongside the rest—or simply sell the rock to the highest bidder.