Malta Feels the Shockwave: UK, Australia & Canada Recognise Palestine—What It Means for the Island

Valletta’s Republic Street was already buzzing with late-afternoon shoppers yesterday when the push-notification lit up phones: the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada will formally recognise Palestinian statehood within the 1967 borders. By the time the church bells struck six, the foyer of the Mediterranean Conference Centre had morphed into an impromptu forum—Maltese students still in their uniforms, Palestinian medical residents still in scrubs, retired British expats still in boat shoes—arguing, hugging, waving both the Maltese and Palestinian flags someone had yanked from a souvenir kiosk.

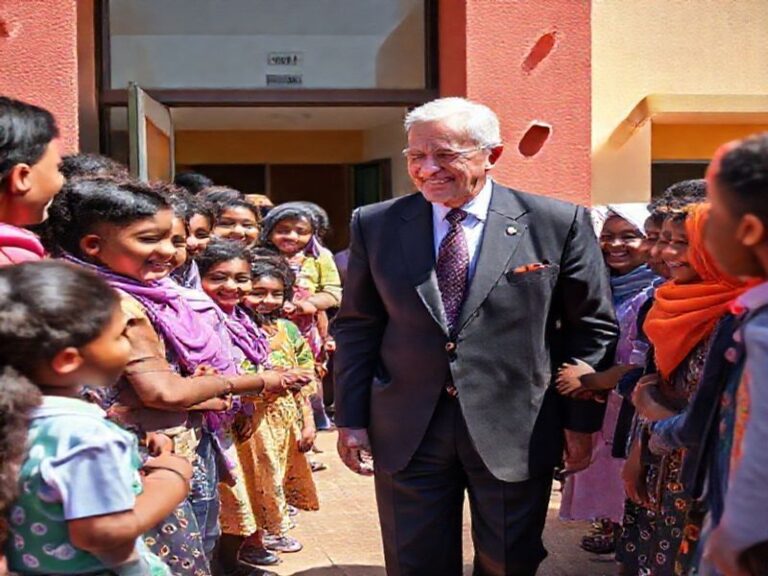

For Malta, the news is more than diplomatic ticker tape. It is the moment a country that has spent 5,000 years trading with every passing empire sees its own bi-cultural DNA reflected in a Middle-Eastern mirror. “We were the bridge between Arab and European civilisations long before CNN existed,” history professor and former ambassador George Vella told Hot Malta. “When major Commonwealth partners pivot on Palestine, Malta feels the tremor first.”

The numbers explain why. According to the National Statistics Office, 3,247 Maltese citizens were born in, or hold dual nationality with, Arab states. Add the 1,800-odd Palestinian students who have graduated from Malta’s medical school since 2010—many of whom stayed on under the “Return Scheme” introduced by Foreign Minister Ian Borg—and you have a micro-diaspora whose WhatsApp groups exploded within seconds of the joint statement from London, Canberra and Ottawa.

At the University of Malta, the Students’ Arabic Society had already printed T-shirts reading “1967 = Justice” by 8 p.m. “We’re not just reacting to foreign headlines,” insisted president Layla Khoury, a third-year pharmacy student whose family fled Bethlehem in 1948. “We’re organising a candle-lit march from Upper Barrakka to the new Palestinian embassy-in-all-but-name on Triq San Pawl, because recognition means our grandparents’ villages finally exist on someone’s map.”

Government reaction was swift but calibrated. Prime Minister Robert Abela tweeted a Maltese proverb: “Min jaħdem mal-ħajt, il-ħajt jgħaddilu idejh”—he who works with the wall, the wall will guide his hands—interpreted by insiders as signalling Malta’s readiness to follow the three Commonwealth states once EU consensus firms. Opposition leader Bernard Grech, meanwhile, reminded parliament that Malta recognised Palestine back in 1988, “before it was fashionable,” and urged the government to lobby Brussels for a unified European position rather than “free-riding on London’s coat-tails.”

Yet it is in the island’s kitchens, not its chambers, that the news tastes strongest. In the narrow alleys of Żejtun, Mariam al-Masri has spent 16 years stuffing vine leaves for her Maltese-Palestinian catering start-up. Yesterday she sold out by noon. “Customers who used to ask for ‘those little green rolls’ now say ‘congratulations on your country,’” she laughed, wiping dill from her fingertips. “Recognition means my son’s teacher will stop calling him ‘the Syrian boy’ and maybe learn to say ‘Palestinian’ without flinching.”

Tourism operators are also recalibrating. Pierre Muscat, CEO of the boutique cruise line SeaMalta, says bookings for Holy-land itineraries have spiked 18 % since the announcement. “Travellers want to be in Jerusalem when history turns the page,” he explained. “Malta is the safest, shortest hop from the EU, so we’re pitching two-night pre-cruise stays in Valletta with Palestinian cultural nights—dabke dancing on the quay, maqluba at the Grand Harbour.”

Not everyone is celebrating. In a corner booth at Café Cordina, 82-year-old war veteran Ċensu Pace nursed a bitter espresso. “I fought in Suez. I’ve seen flags change like bus tickets,” he muttered. “Recognition is words. Words don’t stop rockets.” His sentiment echoes a minority but vocal cohort who fear Malta’s tight-knit Christian community could become collateral to Europe’s wider culture wars.

Still, as dusk settled over the Grand Harbour and the last ferry hooted its way to Gozo, the consensus on the cobblestones was unmistakable: when three of the world’s most influential anglophone states redraw the diplomatic map, a small island that once sheltered St. Paul cannot help but feel the after-shock—and, perhaps, glimpse another chance to live up to its self-styled moniker: the heart of the Mediterranean.