Fontana Priest Takes Gozo to Melbourne: Maltese-Australians Reclaim Language and Legacy

Fontana’s beloved parish priest, Fr. Gabriel Camilleri, has swapped Gozo’s limestone lanes for Melbourne’s tram-lined boulevards this week, touching down in Australia on a three-week pastoral pilgrimage that is already sending ripples of excitement through the Maltese diaspora. The 48-year-old priest, who has shepherded the Fontana flock since 2017, was invited by the Archdiocese of Melbourne to minister to the 40,000-strong Maltese-Australian community, many of whom trace their roots back to the tiny western village famous for its natural springs and centuries-old festa.

Fr. Camilleri’s visit is more than a courtesy call; it is a carefully choreographed cultural bridge. On Sunday he celebrated Mass in Maltese at the Basilica of St. Patrick in Melbourne’s CBD, the first time in two decades that the liturgy has been delivered entirely in the language of the islands. Worshippers arrived hours early, some clutching yellowing black-and-white photos of Fontana’s parish church, others wearing hand-knitted woollen pullovers in the village colours of green and white. “It felt like Gozo had come to us,” said 72-year-old Carmen Azzopardi, who left Fontana on an Italian liner in 1968 and had not heard the village dialect in a sermon since her mother’s funeral. “When Fr. Gabriel said ‘Kelb ta’ San Giljan’ during the homily, half the congregation teared up. That’s our patron saint’s dog—only we know the story.”

The trip was initiated by the Maltese-Australian Social Club in Brunswick, which has watched its membership age and its language fade with each passing year. President Josephine Falzon said they approached Archbishop Peter Comensoli last September, asking for a Maltese priest who could “re-ignite the flame.” Fontana’s mayor, Arch. Horace Gauci, personally recommended Fr. Camilleri, citing his innovative use of Facebook Live catechesis and his restoration of the village’s 16th-century spring chapel. “We wanted someone who understands that being Maltese is not just passport-deep,” Gauci told Hot Malta from his office overlooking Fontana’s main piazza. “Gabriel lives our traditions—he mills his own ħobż biż-żejt olives, he sings the l-Għanja folk songs. He could sell Malta to Maltese who have never seen it.”

Back home, villagers are following the journey with a mixture of pride and technological wonder. The parish Facebook page, usually reserved for festa schedules and wedding banns, has become a live travelogue. Each evening at 7 p.m. Local time, Fr. Camilleri posts a three-minute video titled “Il-Ħanut tal-Lvant” (The Shop of the East), greeting Fontana’s 1,200 residents from quirky Melbourne locations—yesterday in front of a 1920s cable car, today outside a Maltese-run pastizzi pop-up in Footscray that has sold 3,000 ricotta parcels in four days. Primary-school teacher Rita Borg says her students now beg to stay up late “to see if Fr. Gabriel saw any kangaroos.” The village band has even recorded a quick-march titled “Melbourne Farewell” that will debut at next month’s Christ of the Sick procession, complete with didgeridoo sample.

The economic knock-on is already visible. Gozitan handicraft cooperative Ta’ Ċenċ has shipped 500 hand-woven palm-frond crosses to Melbourne, where they are being sold after Mass for AUD $15 each, proceeds split between Fontana’s soup kitchen and Australian bush-fire relief. “We made last year’s entire Easter revenue in one weekend,” coordinator Marica Tabone laughed. “Australians want to touch something their nanna used to braid.”

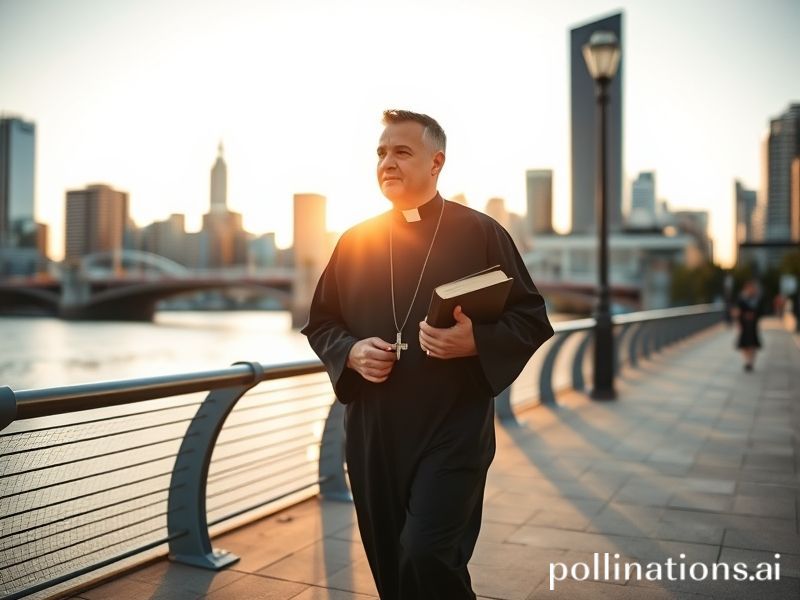

Yet the most profound impact may be spiritual. Fr. Camilleri has been invited to conduct parish missions in Sydney and Perth, and the Vatican’s Dicastery for Migrants is monitoring the visit as a possible template for “diaspora pastoral care.” In a WhatsApp voice note to Hot Malta, recorded while he walked along the Yarra River, the priest sounded buoyant but mindful: “I thought I would bring Malta to them, but they are reminding me what Malta gave the world. These people kept our language alive in desert camps and factory canteens. My job is to hand it back polished.”

When he boards the return flight on 18 July, Fr. Camilleri will carry a digital hard-drive with 200 oral histories, a kangaroo-hide-bound book of intentions, and a petition—already 5,000 signatures strong—asking Archbishop Comensoli to establish a permanent Maltese chaplaincy. Fontana’s bells will ring at touchdown, but the echo will be heard half a world away.