Maltese Virtues: How Limestone, Bread & Ħniena Keep Malta Human

The way we are: our virtues

A small-island survival kit forged by limestone, limestone dust, and each other

Walk down any village core at 06:30 and you’ll hear the first metal shutter rattle up like a church bell in reverse. Someone is sweeping yesterday’s dust off the doorstep, someone else is already arguing—politely—about who last moved the plastic skip. By 07:00 the baker at the corner has slipped an extra ħobż biż-żejt into the bag of the widow who still wears black in July, and the bus driver has waited an extra four seconds for the kid limping with a cello. These are not Instagram moments; they are the daily firmware of Malta, a chain of micro-virtues that keeps 520,000 temperamental CPUs from overheating.

We call it “ħniena”, but the word is too small. It is pity, mercy, neighbourliness and shrewd calculation all at once. It is the reason your pharmacist in Żabbar will deliver your insulin on a Sunday if your surname sounds familiar, and why the same pharmacist will chase you for the receipt because “ma nixtieqx inżommu id-deni”. Our virtues are public-private partnerships: half Gospel, half VAT receipt.

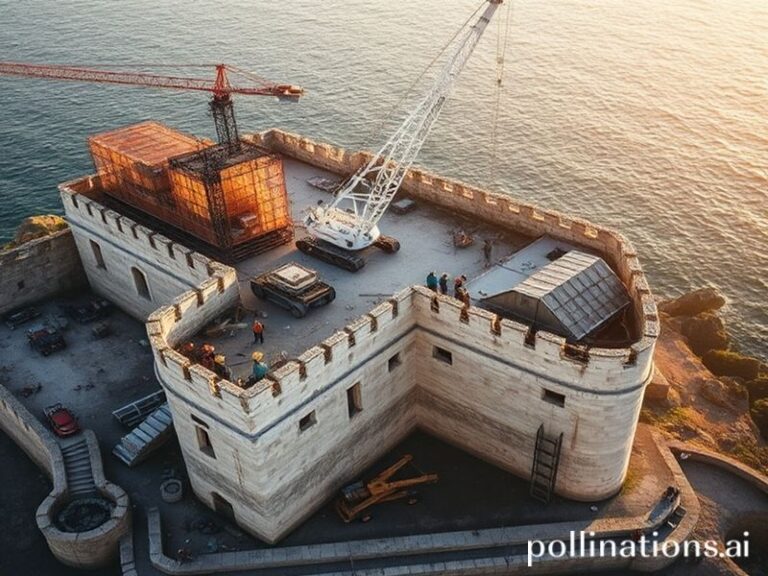

Limestone taught us thrift. When your island is 316 km² you learn to reuse stone, arguments, even feuds. The same balcony corbel becomes a doorstep two centuries later, and the same family grudge is recycled into a village festa rivalry that ends in fireworks and shared beer. Waste is a sin against geography. Hence the national horror of throwing away bread—any nonna will freeze a loaf so stale it could anchor a dghajsa, because “ħobża ma tinxix”.

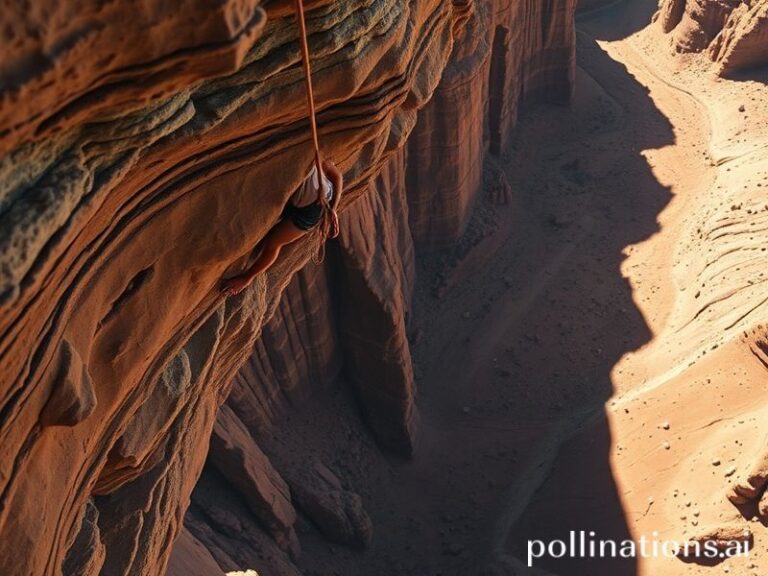

Courage, Maltese style, is not trumpet fanfares; it is the quiet decision to stay. In 1942, with Luftwaffe sorties overhead, the University of Malta refused to close. Students sat in catacombs scribbling notes by candle stub, emerging to find the port in flames and their professors already unloading sacks of flour. That reflex—study while the world bombs your docks—became the seed of today’s iGaming coders who debug from bomb-proof basements in St Julian’s, and the 22-year-old nurse from Għargħur who flew to Bergamo in March 2020 “għax kienu bżonnna”. Staying, or leaving to help others stay, amounts to the same virtue: we do not abandon ship if the ship is the size of a ship-shaped country.

Then there is the virtue nobody advertises: organised cheek. Maltese civic life runs on the assumption that rules are a opening bid. We build boathouses on public land, then landscape them so prettily the ERA gives us a grant. We invent parking spaces where saints once stood, then stick a plastic chair to defend them like a tiny Gibraltar. This is not lawlessness; it is negotiation in 3-D, a survival hack bequeathed by knights, corsairs and British bureaucrats who left us their paperwork but not their winters. The resulting fudge—half regulation, half village consensus—irritates northern Europeans, yet produces cities where fireworks, finance and fenkata coexist within 200 metres.

Critics call these virtues parochial. They miss the upgrade cycle. A Syrian tailor opens shop in Marsa; within a month the local band club is collecting zeppoli money for his daughter’s First Communion. A gay volleyball team in Valletta raises funds for the village feast in Qrendi, because the saint is inclusive if the beer is cold. Virtues once guarded by gatekeeping nonni are being forked on GitHub by teens who code in four languages and still kiss their nanna on both cheeks.

What happens when the island’s software meets global hardware? Sometimes we crash—overdevelopment, money laundering, the occasional minister who confuses ħniena with impunity. But the rollback is already written in our source code: the same gossip network that once shamed a spinster now viral-shames a polluting developer. The village feast that collected coins for the church roof now crowdfunds solar panels for the parish hall. Our virtues are not museum pieces; they are patches, updated nightly by people who argue like siblings because, in a country the size of a large family, that is exactly what we are.

Conclusion

Malta’s virtues are not marble statues; they are limestone, porous and alive, absorbing diesel fumes, sea salt and new accents. They can erode, but they can also be re-carved. If the 21st century is going to be lived on small, crowded, overheating islands, perhaps the rest of the world could do worse than download our patch: share the doorstep, freeze the bread, wait four seconds for the cello, and—when the bombs fall—keep the university open in the dark.