Malta Plants Flag in Ramallah: Inside the Island Nation’s Bold Palestine Diplomacy Move

Malta Appoints Representative to Palestine: A Small Island’s Big Diplomatic Move

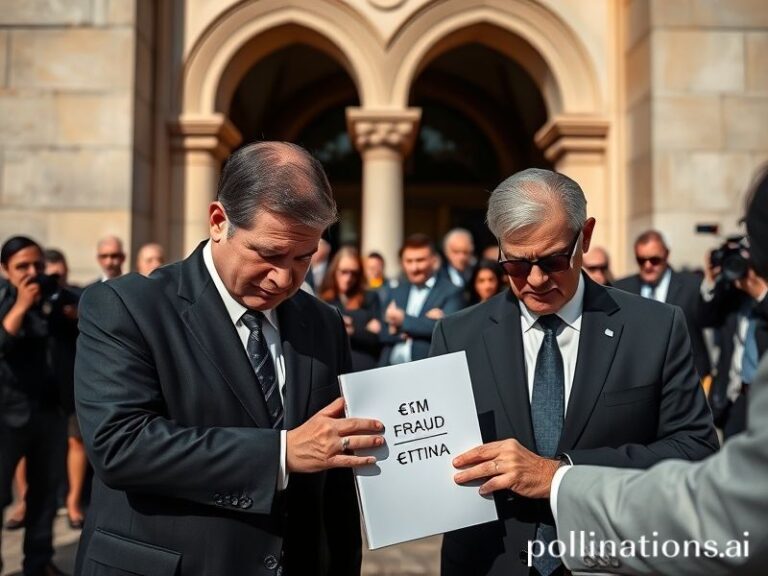

In a quiet but significant diplomatic step, Malta has officially appointed a resident representative to the State of Palestine — a move that places the tiny Mediterranean archipelago at the heart of one of the world’s most intractable conflicts. The decision, announced by Foreign Minister Ian Borg during a recent visit to Ramallah, marks Malta’s first full diplomatic presence in Palestine and signals a shift in how the island nation wields its neutrality on the global stage.

For a country more often associated with sun-soaked beaches and Baroque cathedrals than geopolitical chess, the appointment is no mere formality. Malta, which gained independence from Britain in 1964 and spent centuries as a strategic naval pawn, has long punched above its weight in diplomacy. From hosting Libya peace talks in Valletta’s 16th-century Auberge de Castille to mediating EU migration crises, the island has cultivated a reputation as Europe’s discreet dealmaker. Now, by planting its flag in Ramallah, Malta is betting that its colonial past and post-colonial present give it unique credibility in the Middle East.

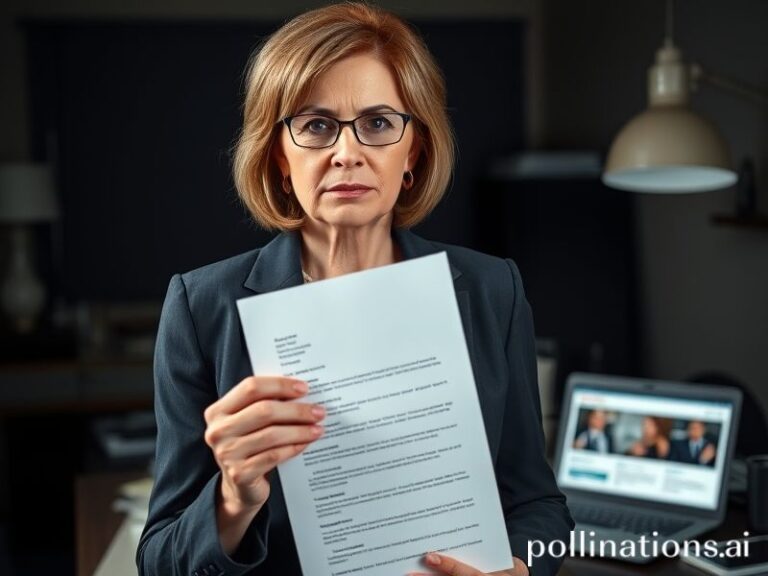

“This isn’t about taking sides,” insists Borg, sipping a cappuccino at Caffe Cordina after returning from the West Bank. “It’s about being present where our values matter — human dignity, rule of law, the right to exist in peace.” The new representative, career diplomat Marisa Farrugia, previously served as Malta’s ambassador to Tunisia and speaks fluent Arabic. She will operate out of a modest villa in Al-Bireh, just outside Ramallah, tasked with deepening humanitarian ties and reporting directly to Marsa’s foreign ministry.

Local reactions have been mixed, reflecting Malta’s complex relationship with the Arab world. In the narrow alleys of Valletta, elderly men playing briscola outside the Phoenicia Hotel recall 1973, when Prime Minister Dom Mintoff welcomed Yasser Arafat for a state visit — the first by any Western leader. “We Maltese understand occupation,” says 82-year-old Ġanni Zahra, whose father fought British colonial troops in 1958. “We’ve been ruled by Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, Knights, French, British… we know what it means to have someone else draw your borders.”

Yet younger Maltese, raised on Instagram images of Tel Aviv beach parties, view the move through a different lens. “Why Palestine and not Israel?” asks 24-year-old influencer Tamara Camilleri, filming reels outside Sliema’s Jewish deli. “My followers want balance, not politics.” Her TikTok poll found 62% of 1,200 respondents “confused” by the decision, with many fearing it could dent Malta’s booming Israeli tourist market — 80,000 visitors last year alone.

Economically, the stakes are real. Israeli tourists spend an average €1,400 per visit, dwarfing the €400 typical Palestinian visitor. But Malta’s Palestinian diaspora, though small at 300 families, has lobbied hard for representation. “Finally, our homeland has a voice in Malta,” says Rania Abu-Zahra, whose Bethlehem-born grandfather opened Mosta’s first falafel kiosk in 1987. Her children, now third-generation Maltese, will perform dabke at next month’s Malta-Palestine Friendship Festival in Floriana — an event expecting 5,000 attendees and live-streamed to refugee camps in Lebanon.

The appointment also reflects shifting EU dynamics. With Sweden, Ireland and Spain recognizing Palestine, Malta risks appearing retrograde if it lags behind. “We’re not recognition — yet,” clarifies Borg. “But presence precedes recognition. It’s the Maltese way: listen first, judge later.” Indeed, Malta’s constitution enshrines neutrality, a legacy of Mintoff’s non-aligned movement days. By embedding a diplomat in Ramallah while maintaining its Tel Aviv embassy, Malta preserves that delicate balance.

For ordinary Maltese, the impact will be subtle but tangible. Palestinian students will find easier visa pathways to Malta’s university; olive oil from Bethlehem will appear on supermarket shelves; and Maltese medics may train in Palestinian hospitals under new twinning agreements. In a country where 15% of the population traces roots to Arab Sicily, cultural resonance runs deep. The appointment feels less like foreign policy than family reunion — a small island acknowledging another small nation’s struggle to exist on its own terms.

As the sun sets over Valletta’s Grand Harbour, the Palestinian flag now flies alongside 27 others outside the foreign ministry. It’s a reminder that in diplomacy, as in life, Malta’s size is irrelevant — what matters is the size of its heart.