EU Slaps Malta with Plant-Health Infringement: Citrus Groves, Hotel Palms and Farmers on Edge

Brussels has bitten back.

On a humid Tuesday morning, while most of Malta was still debating whether the first ħobż biż-żejt of the season needed more ripe tomatoes, the European Commission quietly fired off a letter of formal notice: Malta is being hauled into EU court for failing to police the very plants that paint our terraced islands green.

The charge-sheet reads like a gardener’s worst nightmare: citrus trees shipped without passport-style plant-health certificates, imported palm palms that may be harbouring a killer beetle, and a national surveillance system the Commission brands “patchy at best”. In EU-speak we now have two months to reply or we move to the next, wallet-draining stage of infringement. Fines start at €90 000 a day—enough to irrigate every farm in Wied il-Għasel for a decade.

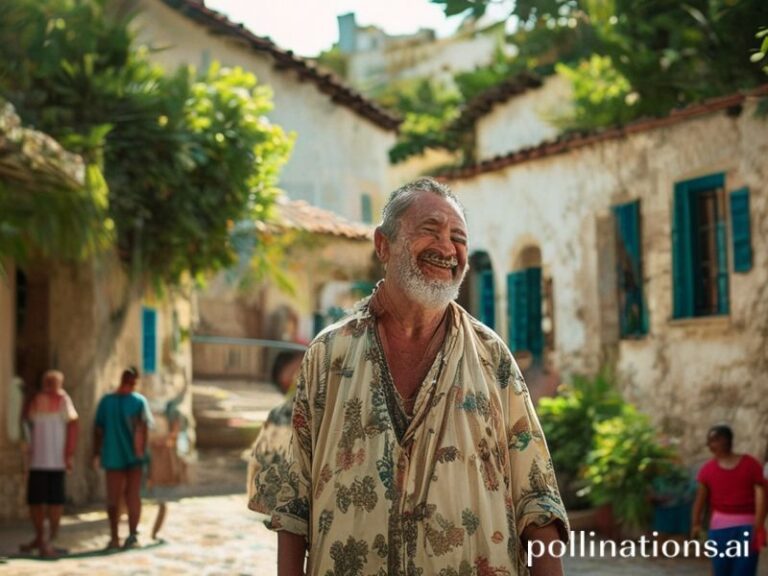

Local farmers, still jittery after last year’s tomato-virus wipe-out, greeted the news with a collective “u iva, mhux l-ewwel darba” (“yeah right, not the first time”). But beneath the shrug lies real fear. “Our oranges are our identity,” says 68-year-old Carmenu Zahra, pruning his family’s 200-tree grove in Rabat. “If Brussels slaps us because someone else cut corners on paperwork, it’s us growers who’ll pay the surcharge.”

The cultural stakes are higher than a carob tree. Maltese citrus isn’t just export revenue—€4.7 million last year—it’s village festa centre-pieces, the zest in kusksu soup, the perfume of a thousand courtyard gardens. The iconic lumi l-Ġdid (Maltese blood orange) is so tied to winter that housewives time their marmalade by its blush. Lose market access and we lose more than fruit; we lose chapters of our living folklore.

How did we get here?

Sources inside the Agriculture Ministry whisper that staffing at the Plant Health Directorate has been frozen since 2020. With only nine full-time inspectors to cover 316 square kilometres, plus the freeport conveyor-belt of imported ornamentals, corners get cut. “We flag suspect shipments, but by the time the paperwork catches up the palms are already gracing hotel lobbies in St Julian’s,” one inspector admitted, requesting anonymity.

The timing is excrucious. Summer tourism is rebounding, and every balcony geranium, every golf-course oleander, is a potential host for Xylella fastidiosa—the bacterium that turned Puglia’s olive groves into graveyards. Scientists warn our climate is a welcoming runway for the pathogen. “One infected oleander on the Sliema front could jump to the citrus belt in two seasons,” says plant pathologist Dr Rebecca Vella. “Malta is basically one big greenhouse; once disease takes off, forget containment.”

Hoteliers are watching nervously. Five-star resorts spend six-figure sums landscaping entrances with exotic palms precisely so guests can Instagram that “Mediterranean vibe”. If Brussels forces a ban on high-risk imports, landscaping bills will triple, and operators fear tourists will decamp to competing islands where the palm-lined pool shot is still possible.

Yet the Commission’s letter may be the wake-up call we needed. Agriculture Minister Anton Refalo reacted fast, pledging a €3 million “Plant Health Shield” that includes mobile labs at the airport and a 24-hour quarantine warehouse at Malta Freeport. “We will turn this infringement into an opportunity to become the smartest plant-health island in Europe,” Refalo declared, perhaps forgetting that opportunities usually arrive before the fines.

In village bars, opinions are split. Some farmers want tougher checks—even if it means slower imports—while others blame “Brussels bureaucracy” for nit-picking. But everyone agrees on one thing: the real test is enforcement. A gleaming new lab is useless if an inspector can be persuaded to look the other way for a crate of contraband kumquats.

Conclusion

Malta’s tiff with Brussels is more than a bureaucratic squabble; it is a referendum on how much we value the greenery woven into our folklore, economy and daily bread. If we emerge with stricter surveillance and smarter science, the lumi l-Ġdid will keep tinting winter skies orange and hotel guests will still sip rum under imported palms. If we don’t, the next infringement letter could carry a price tag big enough to wither every terraced orchard from Għammieri to Għarb. The choice, like a perfectly timed pruning cut, is ours to make—before the EU makes it for us.