Fortina’s fortune: how a tiny Sliema cove became Malta’s five-star village

Fortina’s fortune: how a sleepy fishing cove became Sliema’s golden mile

By Hot Malta staff

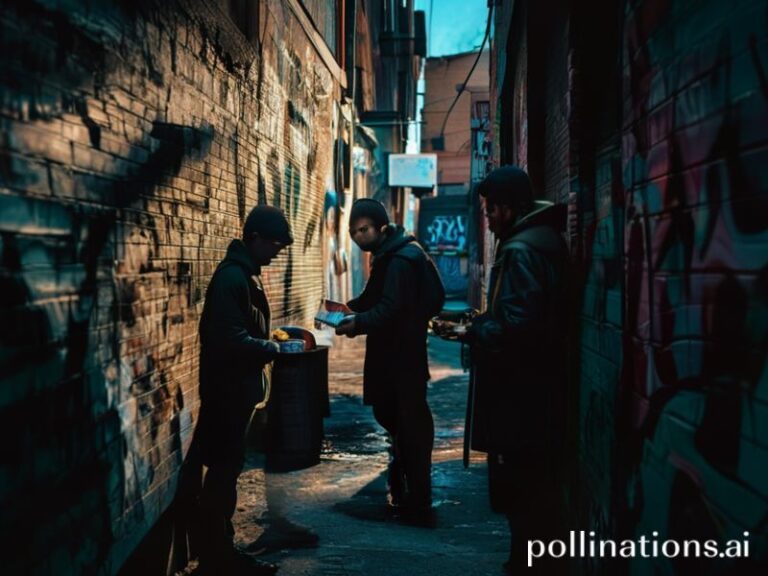

Walk along the Sliema promenade at 6 a.m. And you’ll still see the last lamp-lit silhouettes of elderly Kalkara men folding their nets where, 400 years ago, the Knights’ galleys off-loaded grain for Valletta’s granaries. By 7 a.m. The same stretch is a parade of neon lycra, French bulldogs and foreign joggers heading for the first flat-white of the day. Somewhere between those two Maltese mornings lies the story of Fortina: the tiny cove that learnt to print money without ever forgetting whose sea it is.

From bastion to boutique

The name comes from the diminutive fort the Knights threw up in 1715 to plug the gap between Tigné and Spinola. Locals called it “il-Fortina” – the little fort – and the label stuck even after Napoleon’s guns turned it to rubble. For two centuries the inlet remained a quiet appendix where Sliema housewives rinsed carpets in the winter swell and kids competed to leap off the “għażżien” rock. Then, in 1968, a young contractor from Birkirkara named Joseph G. Fenech bought a derelict artillery store for Lm 3,000 (€7,000) and painted it pink. The Fortina Restaurant opened with six tables, a one-burner stove and a view no menu in Malta could match. Within a year ministers were queuing for lobster thermidor; within five, Fenech had enough profit to lobby for the first hotel licence outside St Julian’s. The 42-room Fortina Hotel opened in 1976, the same year Malta adopted the metric system and colour TV. For islanders it felt like the future had docked in their backyard.

The skyline that split a village

The real earthquake came in 1997 when the family unveiled a €60 million redesign: five inter-linked blocks, glass elevators cantilevered over the water, and a penthouse suite that piped seawater straight into the bath. Suddenly Fortina wasn’t just a postcode; it was a verb – “qiegħda tFortina” meant you had arrived. Rents in the surrounding grid of Victorian townhouses tripled; traditional lace balconies were swapped for aluminium shutters painted “Fortina terracotta”. Not everyone applauded. “We lost the smell of seaweed to the smell of sunscreen,” says 73-year-old Toni “il-Bos” Vella, who still keeps his father’s wooden boat in the adjoining creek. “But we also lost the smell of poverty, so pick your poison.”

Cash registers and confessionals

Today the Fortina precinct employs 450 staff – 70 % from the 1613 and STC postal codes – making it Sliema’s largest private employer outside the retail chains. Kitchen porter Clayton Mifsud, 26, swapped a gig economy delivery scooter for a full-time contract with health insurance. “My nanna lights a candle to St Cajetan every Sunday because I no longer work Sundays,” he laughs. Across the road, parish priest Fr. Anton D’Amato negotiated a 30 % discount on heated corridors for the adjacent Stella Maris retirement home, funded by the hotel’s annual charity gala. Last Christmas the same gala raised €112,000 for Puttinu Cares – enough to airlift three children to London for leukaemia trials. “Tourism with a conscience” sounds like marketing fluff, but in a country where 30 % of GDP depends on the industry, the numbers preach louder than sermons.

The price of postcard perfect

Success has brought its own tides. Residents’ association president Claire Zammit says short-term lets have hollowed out 40 % of the neighbourhood’s long-term housing stock. “We live in a goldfish bowl where the fish pay €200 a night,” she sighs. Waste-water overflow last August turned the bathing zone amber; environmental NGOs blame the 600 daily spa users for overloading the antique sewers. Yet when the hotel offered to fund a €2 million reverse-osmosis pipeline, the same NGOs sat at the table. “You can’t unscramble an omelette,” admits Ramona Depares from Friends of the Earth, “but you can add better eggs.”

Sunset on the silver mile

This summer Fortina will unveil a €15 million rooftop solar farm disguised as terracotta shingles, enough to power the entire complex and 200 neighbouring households. Guests will scan a QR code to see how many kilowatts their breakfast toast consumed. Meanwhile Toni “il-Bos” still launches his clinker-built boat every dawn, guiding German photographers past the infinity pools for that money-shot of Malta old-and-new. “They want authenticity,” he winks, “so I charge extra for the frayed rope.”

Conclusion

Fortina’s fortune is Malta in microcosm: a knights’ ruin reborn as a five-star playground, where the scent of frying lampuki mingles with SPF 50 and the parish bell competes with chill-out house. It has made us richer, brasher and, arguably, kinder. Whether that little cove can keep its soul while printing euros faster than a Central Bank mint is the next chapter – one that will be written not in glossy brochures but in the salt-crusted diaries of the people who still call Sliema home.