Malta’s Second Energy Lifeline: New Sicily Cable Promises to End Summer Blackouts Forever

Malta Plugs Into Europe: Second Energy Lifeline Begins in Sicily

The dusty coastal roads of Ragusa, Sicily, are humming with Maltese anticipation this week as engineers break ground on the island-nation’s second electricity interconnector—a 120-kilometre umbilical cord that will tether Malta more tightly to the European grid than ever before. For a country that spent centuries lighting its nights with olive-oil lamps and praying for coal ships to outrun storms, the moment feels almost biblical: a tiny archipelago, once the lantern of the Mediterranean, now threading its future beneath the same sea that carried Phoenician traders and Napoleonic galleons.

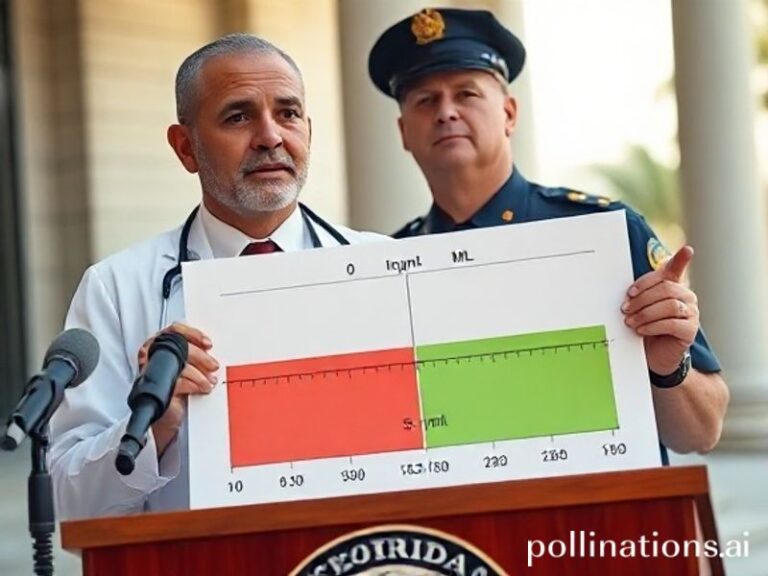

“Every spade of Sicilian soil is a promise that our children won’t have to choose between air-conditioning and industry,” Energy Minister Miriam Dalli told Hot Malta from the construction site, hard-hat clipped over her bobbed hair. The €170 million project—officially dubbed the Malta–Sicily Interconnector 2 (MSI2)—will run parallel to the existing 200-MW cable laid in 2015, doubling import capacity to 400 MW and, officials insist, slashing the risk of summer blackouts that have haunted Maltese households since the 1980s.

Yet beyond the megawatts and market jargon, the cable is stitching together something less quantifiable: a cultural reconnection with the island we quietly call “il-fratellino,” the little brother. Sicilian and Maltese workers share cigarettes in the shadow of cranes, swapping recipes for rabbit stew and arguing over whose dialect mangles Italian vowels more spectacularly. “My nonna used to listen to Malta’s Rediffusion radio while rolling gnocchi,” laughed Carmelo Insanguine, a Ragusa electrician hired for the marine survey. “Now I’m literally powering her favourite island—history unplugged and plugged back in.”

Back home, the symbolism is not lost on a population whose national anthem pleads for God to “give light to Malta.” In Valletta’s narrow alleys, elderly men replay memories of 1973’s oil crisis when Prime Minister Dom Mintoff negotiated emergency power from Sicily via a temporary overhead line strung on war-surplus pylons. “We called it ‘il-wajer tal-imħabba,’ the love wire,” reminisced 81-year-old Toni “il-Pampalun” from his customary perch outside Café Cordina. “Every time the lights flickered, we knew Italy was hugging us.”

Today’s cable is less romantic but more resilient: buried two metres below the seabed, armoured against anchors and earthquakes, monitored by drones that tweet alerts in real time. Still, the nostalgia lingers. Gozitan artist Pawlu Camilleri plans to cast a bronze sculpture from the first reel of surplus copper, shaping it into a traditional dgħajsa ferryman holding a lightning bolt instead of an oar. “We’re rowing into the future with electrons instead of sweat,” he explained, paint on his hands from the preliminary mould in his Xewkija studio.

Not everyone is toasting with Cisk. Environmental NGO Moviment Graffitti warns that cheaper imported electricity could delay Malta’s transition to rooftop solar and offshore wind. “The easier you make it to import power, the lazier governments become about home-grown renewables,” argued spokesperson Claire Bonello. Her fears echo across Facebook groups where residents share €300 summer bills like battle scars. Yet even sceptics concede that Malta’s land scarcity makes large renewable farms a pipe dream; importing clean electrons from Italy’s burgeoning solar farms may be the lesser evil.

In Ragusa, the drilling ship Nautilus has become an unlikely tourist attraction. Sicilian families picnic on the cliffs, photographing the Maltese flag fluttering beside the Tricolore. Someone’s nonna sells ħobż biż-żejt from a trestle table, swapping the usual tomato paste for sun-dried Sicilian pomodoro. “We’re building a bridge you can’t see,” project engineer Rebecca Vella shouted over the roar of engines, her Maltese lilt rising above the Mediterranean wind. “But every time a Maltese child turns on a light without asking Mum if we can afford it, they’ll feel it.”

By 2027, when the 140-tonne converter stations are blessed by bishops on both shores, Malta will draw up to 70 % of its electricity from Europe—enough, planners say, to power 250,000 homes or 450,000 electric cars. The cable will lie silent, invisible, like the submerged heritage of temples and shipwrecks beneath it. Yet its current will pulse with stories: of Sicilian and Maltese hands splicing fibres in the dark, of grandmothers who once huddled around candle-lit radios now binge-watching Netflix powered by the same stretch of sea.

As the sun sets over Ragusa’s baroque skyline, the construction lights flicker on—powered, for now, by diesel generators. Two kilometres beneath the swell, a copper vein waits to awaken. And somewhere in Sliema, a teenager charges her phone without a second thought, unaware that her next TikTok scroll will ride a wave born in Sicilian dust and Maltese dreams. The second interconnector is more than infrastructure; it is Malta’s quiet declaration that the days of island solitude are over. We are no longer the lamp in the storm, but the current that lights the continent—one volt at a time.