Malta’s Heart Breaks for Nameless Boy Washed Up in France: How One Migrant’s Death Reopens Island’s Oldest Wound

Dead on a Foreign Shore: How a Migrant’s Tragedy in France Echoes in Malta’s Living-Rooms

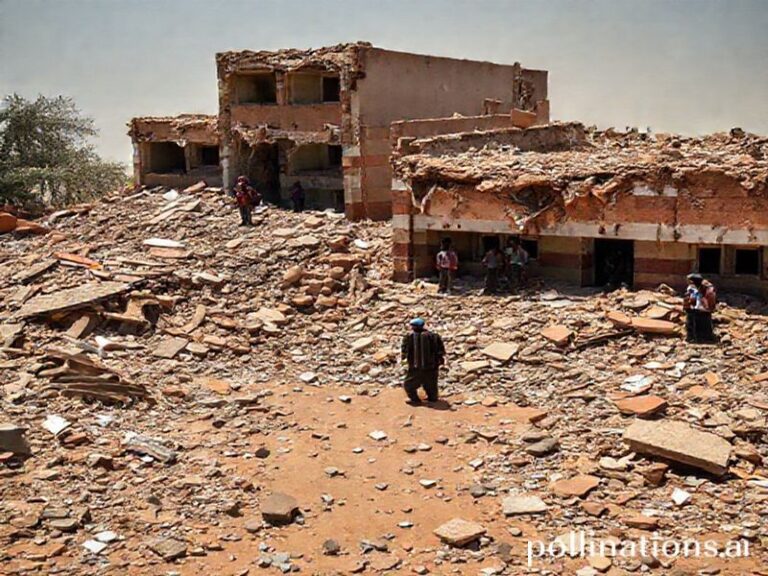

By 7 a.m. On Tuesday, the WhatsApp forwards had already landed in Birkirkara, Żabbar and Sliema: a blurred photo of a young man in soaked denim, face turned to the sky on a windswept Normandy beach. By noon, Maltese Facebook groups were arguing over whether he was “one of ours” or “just another statistic”. By sunset, the island’s migrant-led NGOs had lit a candle-row outside the Phoenicia gates, proof that a death 2,000 km away can still bruise a rock whose shores have seen 32,000 irregular arrivals since 2002.

French authorities have not released the boy’s name—only his age, 17, and the fact that the dinghy he shared with 48 others capsized in four-metre waves off Berck-Plage shortly after 3 a.m. Two survivors told Médecins du Monde that the teenager had clutched a cracked power-bank on which he’d saved the offline map of Malta, ringed in red like a childhood treasure island. Whether Malta was ever his destination or simply the last European dot he could name is irrelevant; the island has become the Rorschach test for every migration tragedy in the central Mediterranean.

In the tight lattice of Valletta side-streets, the news reopened a wound that never quite scars. “We are, again, the mirage that kills,” sighed Carla Camilleri, a lawyer who has represented Maltese-flagged merchant crews sued for “illegal rescue” after plucking migrants from flotsam. Her phone pinged with voice-notes from three different captains currently at sea: “Do we divert if we spot another grey rubber boat? The French boy makes the calculus harder; owners fear liability more than ever.”

The timing is politically pungent. Parliament is debating the government’s new fast-track asylum procedure, which NGOs say will fingerprint and ferry migrants back to Libya within 72 hours. Opposition MP Joe Ellis, who once volunteered on the NGO vessel *Aquarius*, brandished a print-out of the Normandy corpse in committee. “This is where deterrence ends—in a body bag on a beach that exports oysters, not humans.” The Speaker asked him to sit down; the image, already viral, had done its damage.

Yet beyond the macro-politics, the tragedy has slipped into the micro-fabric of Maltese neighbourhoods where newcomers and old-timers already share balconies, bakeries and feasts. In Marsa, Guinean barber Mohamed Condé closed shop early to attend the vigil. “I crossed in 2019. The boat behind us vanished. When I saw the French photo I smelled the petrol again,” he told *Hot Malta*, voice cracking. “Here we drink Kinnie, we speak Maltese, we pay VAT—but the sea is still our courtroom.”

At the University of Malta, anthropologist Dr Graziella Vella says the island’s “cultural muscle memory” of emigration—150,000 Maltese left for Australia, Canada and Algeria between 1946 and 1980—makes each migrant death feel like a distorted family album. “Our grandparents sailed on £10 tickets; these kids sail on €1,000 smuggler invoices. The ocean is the same referee, just wearing new goggles.”

Local band Club Europa has turned the boy’s unnamed story into a three-chord ballad already racking up Spotify streams. Lyrics reference Maltese lace, French seaweed and “a power-bank that died before the boy did”. Meanwhile, the parish priest of St Julian’s has added a new intention to the Sunday mass: “For the child who believed our limestone was mercy.”

Will anything change? The European Commission’s new Malta-Tunisia deal, leaked yesterday, promises more drones, more razor wire, more “pre-frontier interdiction”. But on the ground, the conversation feels older and rawer. At the Valletta vigil, a teenage girl laid down a hand-written placard: “He had our flag in his pocket and we still said no.”

As storm clouds gathered over the Grand Harbour, the candles hissed out one by one, wax pooling on the granite like salt tears. Somewhere in France, an autopsy began; somewhere in Malta, a conscience still refuses to end.