Floriana’s Rooftop Summer Festival: From Mozart to Camilleri Under the Stars

Rooftop Series Summer Festival to play Mozart to Camilleri in Floriana

======================================================================

Floriana’s historic skyline is about to become the island’s most glamorous open-air concert hall. On four consecutive Fridays this July, the Ministry for National Heritage’s “Rooftop Series” will plant audiences on the terraced roofs of the 18th-century Argotti Gardens and the adjacent Casino Notabile, threading classical strings, jazz riffs and Maltese brass through the limestone balustrades that once guarded Valletta’s outer walls. The programme leaps three centuries in a single breath: Mozart’s Linz Symphony shares the sunset with Charles Camilleri’s Malta Suite, while home-grown composer Euchar Gravina premieres a new work scored for saxophone and vintage motorcycles—an audible love-letter to the antique engines that still growl along Floriana’s tree-lined avenues.

For a village that has spent the last decade reinventing itself from traffic-choked commuter corridor to cultural quarter, the festival is the latest rooftop brick in a patient wall of soft-power regeneration. “We want people to rediscover Floriana as a place to linger, not just pass through,” says local councillor James Aaron Ellul, who has spent lockdown lobbying for pedestrian-friendly access to the gardens. “When music drifts over the bastions, the whole neighbourhood remembers why these stones matter.”

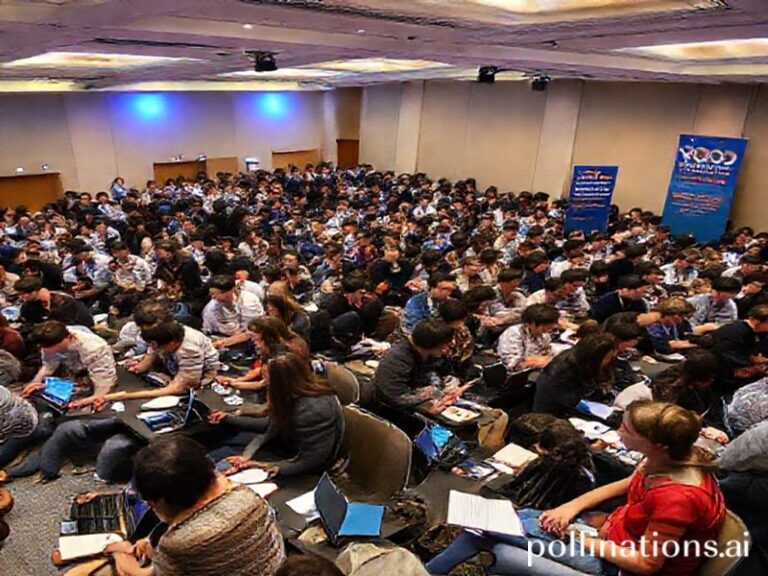

The concept is elegantly simple: 250 ticket-holders climb a candle-lit staircase to the Argotti’s upper terrace at 19:30, prosecco in hand, and watch the Grand Harbour melt from gold to violet while a 15-piece ensemble plays. Because the gardens sit slightly lower than Valletta’s ramparts, the city becomes a floating stage set—cathedral dome on the left, cruise-ship funnels on the right, and, dead ahead, the ghost of the old Sacra Infermeria where wounded knights once listened to lutes instead of violins.

Cultural significance runs deeper than Instagram aesthetics. The festival pairs Western canonical staples with Maltese voices deliberately sidelined in previous centuries. Camilleri’s 1956 suite—rarely performed on the island since its BBC premiere—will echo across the same harbour that inspired its għanja-inspired motifs. “We’re rewriting the canon inside the canon,” explains artistic director Michelle Castelletta, who also leads the Malta Philharmonic’s outreach wing. “Every crescendo is a reminder that ‘classical’ isn’t an import duty; it’s a living Maltese dialect.”

Community buy-in has been meticulous. Floriana primary-school children painted the stage floor with cobalt crosses borrowed from the village flag; their parents will staff the bar in exchange for free rehearsal passes. Two social-housing blocks overlook the terrace, and residents have been promised balcony seats and a dedicated speaker channel so that pensioners can enjoy the concert without leaving home. “Usually we complain about noise,” laughs 82-year-old Tereża Borg, who has lived on St. Anne Street since 1964. “This time we’re complaining if the music stops.”

Economically, the ripple is already visible. Boutique guest-houses tucked into converted townhouses report 90 % occupancy for festival weekends, while nearby cafés have extended menus to include late-night ftira topped with rabbit ragu—an edible bridge between peasant tradition and cosmopolitan appetite. Even the parish priest has joined the marketing effort, announcing post-concert organ meditations inside the baroque church of St. Publius, hoping to lure culture tourists into spiritual sidebar events.

Yet the festival’s boldest statement may be ecological. All lighting is solar-powered, collected during June’s longest days and stored in discreet battery packs hidden behind oleander pots. Single-use plastic is banned; programmes are printed on seed-paper that audiences can later plant in their balconies, sprouting thyme and wild fennel that once carpeted the harbour’s surrounding hills. “Culture should compost, not consume,” quips project manager Lara Calleja, who previously coordinated Valletta’s European Capital of Culture green squad.

Weather contingencies are characteristically Maltese: if the sirocco whips up, musicians will retreat to the Casino Notabile’s vaulted saloon, where 19th-century British officers once gambled away regimental funds. The acoustics, technicians swear, are even better indoors—dry enough to hear the gut-string growl of a viola da gamba, yet warm enough to soften Camilleri’s dissonant clarinet chords.

By August the rooftops will fall silent again, returning starlings and policemen to their usual duet. But something will have shifted. A village that many Maltese only associate with carnival floats and football derbies will have offered proof that heritage is not a mausoleum; it is a terrace we can stand on together, glass raised to the past, playlist queued for the future.