Maltese Scientists Give 3D-Printed Titanium a Dazzling Baroque Make-Over with GLAM Tech

**From Knights’ Armour to Space Age: How Maltese Scientists Are Giving 3D-Printed Titanium a GLAM Make-Over**

*By our science & culture correspondent*

Valletta’s golden limestone façades have reflected every era—from the bronze cannons of the Knights to the carbon-fibre drones that now hover above Grand Harbour. Yet behind the baroque balconies a quieter revolution is taking place: Maltese researchers have just cracked how to make 3D-printed titanium shimmer like silk, feel like ceramic and resist corrosion like the bastions themselves. The EU-funded project, cheekily christened “GLAM” (Generative Laser Aesthetic Morphing), is being piloted at the University of Malta’s new Materials Research Lab in Msida, and it could redraw everything from surgical implants to souvenir daggers.

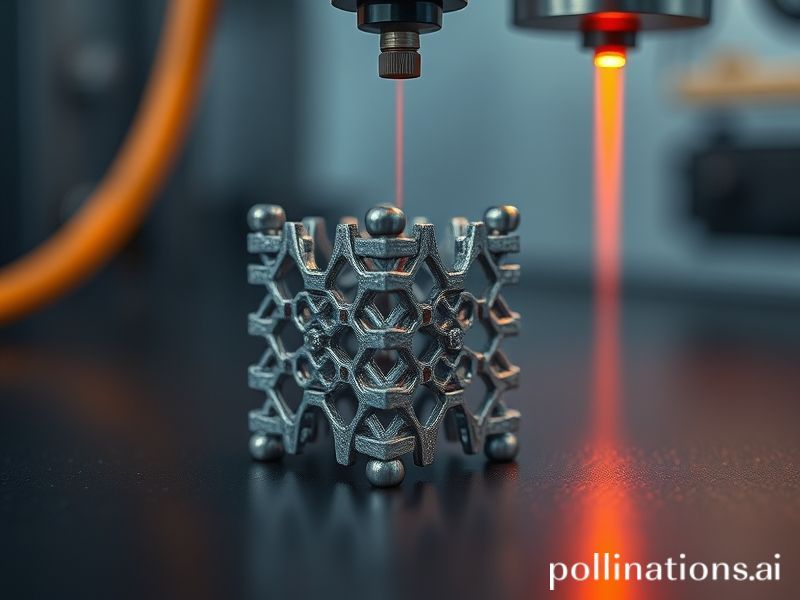

Titanium is already the darling of aerospace and medical start-ups on the island; it’s light, strong and bio-compatible. But the powder-bed printers that fuse layer upon metallic layer leave a dull, oatmeal-grey finish that screams “industrial”. Surgeons dislike it because bacteria hide in the roughness. Jewellers dismiss it because even the brightest buffing wheel can’t coax a sparkle. Enter GLAM: a post-print laser sweep that re-melts only the top few microns, freezing into nano-ripples that bounce light like the inside of an abalone shell. The result? A spectrum of iridescent blues, purples and sunrise golds—colours that shift as you tilt the part—without a single drop of dye or toxic plating bath.

Dr. Ariadne Xuereb, the 32-year-old Sliema native leading the team, still sounds giddy when she recalls the first successful run. “We pulled the bracket out at 3 a.m. and it looked like something stolen from St. John’s Co-Cathedral—exactly that Maltese mix of baroque drama and sea-light.” Her group tweaked the laser rhythm so the ripples mimic the fan-shells painted by Caravaggio in the Oratory. “We’re literally encoding heritage motifs at the scale of a thousandth of a human hair,” she laughs.

Why should islanders care? Because GLAM slashes two headaches that have haunted local manufacturers: post-processing cost and environmental guilt. Traditional polishing of a single hip-implant can take 45 minutes, gallons of acidic slurry and a technician’s full shift. GLAM finishes the same piece in 90 seconds using only light. With Malta’s medical-device exports topping €1.2 billion last year, shaving even 5 % off production time translates into millions—and greener balance sheets that align with the government’s 2030 carbon-neutral pledge.

But the cultural ripples go deeper. In a country where filigree silver and brass door-knockers are passed down like heirlooms, metal carries memory. GLAM opens the door to 3D-printed rosary beads that capture the colours of the Gozo sunset, or custom dagger hilts for the village festa that glow like stained glass. Heritage NGO Din l-Art Ħelwa has already approached Xuereb about replicating a damaged 17th-century candelabrum from the Mdina Cathedral Museum; the replica would be light enough for tourists to handle, yet retain the original’s rainbow patina caused by centuries of candle soot.

Then there’s the human story. Inside the lab, intern Jeremy Saliba, 22, from Żabbar, is calibrating a machine the size of a pizza oven. “I grew up watching my dad weld boat propellers by hand,” he says. “Now I’m programming lasers to paint with light. My parents thought 3D printing was sci-fi—today my mum wants a GLAM bracelet for her festa outfit.” The project has trained 14 Maltese technicians, half of them women, in advanced laser optics, a skill set the European Space Agency is eyeing for satellite components that must survive extreme temperature swings.

Not everyone is star-struck. Traditional jewellers in Valletta’s old jewellers’ street fret that “printed rainbows” could cheapen craftsmanship. Vince Pace, third-generation goldsmith, strikes a cautious note: “A laser can’t replace the hammer marks that tell you a Maltese cross was raised by human hands.” Xuereb counters that GLAM isn’t mass-market plastic tat; each piece can be parameter-tweaked, making every swirl unique—arguably more bespoke than a casting mould used hundreds of times.

For now, the lab is partnering with local start-up Tritan MedTech to print coloured jaw-implants that surgeons can customise to skin tone, reducing the psychological shock for recovery patients. Meanwhile, Malta Enterprise has fast-tracked a €2 million scale-up grant, betting that GLAM can attract aerospace suppliers looking for lightweight, corrosion-resistant brackets for next-generation aircraft—possibly even the flying taxis planned for Malta’s vertiport testbed.

As the sun sets over Msida creek, Xuereb locks the lab door but leaves the corridor lights off; the titanium samples glow faintly on the shelf like captured fireflies. “We’re not just printing metal,” she says. “We’re printing the colour of Malta itself—sun on limestone, storm over Filfla, the violet inside a prickly pear. And for once, the world will see our island not just for its past, but for the future it can forge.”