Paola’s €14 Million Health Hub Opens: From Cramped Clinic to Cultural Landmark

Paola’s 60-year-old health centre closed its doors for the last time at 7 p.m. on Friday, and by Monday morning patients were already being greeted by sunlight, potted lavender and a bar-code check-in kiosk at the town’s new €14 million Primary Health Hub. The shift, which transferred 22,000 medical files overnight, marks the biggest upgrade to Malta’s public front-line care since the 1970s and is being read by residents as more than a bureaucratic shuffle—it is a cultural hand-over from post-war charity clinics to a state-of-the-art, EU-funded health architecture that Paola—Malta’s “town of band clubs and fireworks”—can finally call its own.

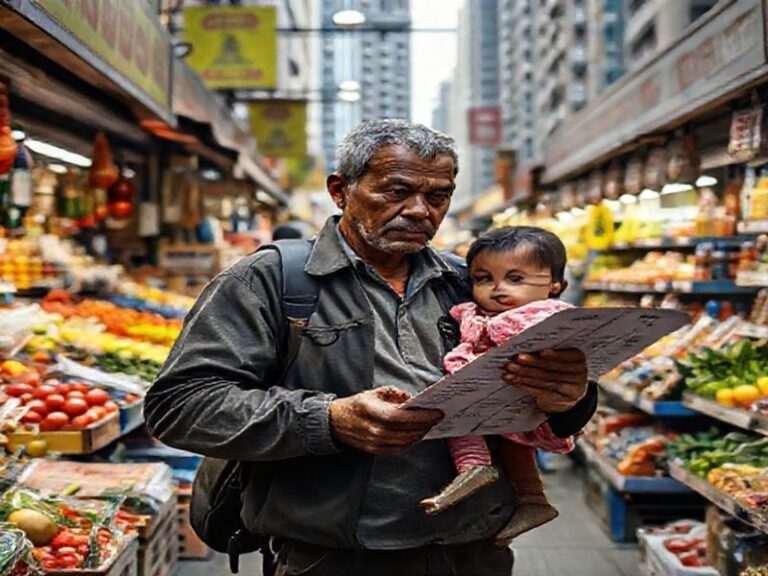

“Il-klinika l-qadima kienet qisha grotta,” laughs 78-year-old Ġorġ Cassar, who has collected prescriptions there since the days of district nurses in starched veils. “You climbed two steps, grabbed a paper number, and hoped the roof fan worked. Today I walked on non-slip tiles, spoke to a triage nurse in Maltese, and had my ECG printed before I even sat down.” Cassar’s nostalgia is typical in a località whose identity is stitched to migration stories: Paola absorbed dockyard workers from the Cottonera, British-services families from Ħal Far, and, more recently, African and Balkan newcomers who swell the population to 10,000 every daylight hour. The old clinic, wedged between a 19th-century chapel and the market square, simply ran out of corners.

Enter the Hub: a two-storey, sandstone-and-glass block built on the site of the abandoned Trade School, a parcel of land that had become an urban pothole teenagers used as an illegal motocross track. Mayor Dominic Grima admits the turnaround felt cinematic. “One summer we were lobbying for noise barriers, the next we’re cutting a ribbon with Deputy Prime Minister Chris Fearne and EU Commissioner Helena Dalli,” he says. “But the real plot twist is that Paola is no longer the place you drive through to reach the airport; it’s a destination for care.”

Inside, the hub houses six GP pods, two dental surgeries, a breast-feeding lounge plastered with Żabbar crib figurines (a nod to local artisan culture), and a rooftop terrace that will double as a community garden managed by the parish youth group. Digital tablets allow patients to choose their preferred language—Maltese, English, Italian, Arabic, Somali—reflecting Paola’s linguistic patchwork. A mini-pharmacy run by the Malta Pharmaceutical Students’ Association offers Saturday morning “brown-bag reviews” where seniors unpack their medication to check for dangerous overlaps; it’s already booked solid through July.

Cultural significance runs deeper than bilingual signage. The clinic’s façade incorporates a perforated aluminium screen laser-cut with the pattern of the traditional Maltese tile, a motif that glows amber at dusk and has become an Instagram favourite. Architect Maria-Grazia Cassar (no relation to Ġorġ) explains: “We wanted the building to read like a band club—open, lit, humming with life—rather than a place you only visit when fever strikes.” Across the road, the parish priest has agreed to ring the church bells at 11 a.m. each weekday, a sonic cue that the hub’s wellness walk-in session is open, marrying religious time to public-health routine in a way only Malta could.

Early data show impact. In the first week, 1,300 patients were seen; 42% had never registered with a regular GP, suggesting the hub is reaching the invisible cohort of casual labourers and undocumented migrants who previously waited until midnight to appear at Mater Dei’s emergency department. Waiting time for routine blood tests has dropped from 19 days to 72 hours. Most tellingly, the no-show rate—historically 28% in inner-harbour clinics—fell to 9%, attributed to SMS reminders in patients’ mother tongues and free Tallinja bus vouchers dispensed at reception.

Yet challenges linger. Some elderly patrons complain the self-check-in screen is “tal-ġenn” (madness), and kiosk assistants have been rechristened “technology translators.” Others fear the hub will gentrify Paola’s rental market. “If the place looks too fancy, landlords will hike prices,” warns Mariama Bah, a Guinean mother of two who has lived in a two-room flat near the mosque since 2014. Deputy Fearne counters that 30% of hub staff have been recruited from Paola itself, anchoring salaries—and lunch-time spending—in the town’s economy.

For now, optimism prevails. On opening day, children from the nearby Paola Square primary school presented doctors with paper cranes inscribed with health wishes in Maltese and Tigrinya. Someone pinned a hand-written note to the noticeboard: “Grazzi, Paola, għax issa għandna futur ukoll.” (“Thank you, Paola, because now we also have a future.”) In a country where health care can feel like a tug-of-war between private gloss and public grind, the Hub offers something rarer than robotics: dignity, delivered round the corner from the pastizzi kiosk. If the cranes stay aloft, Paola’s next 60 years may be measured not in waiting lists but in bell-rings and rooftop tomatoes.