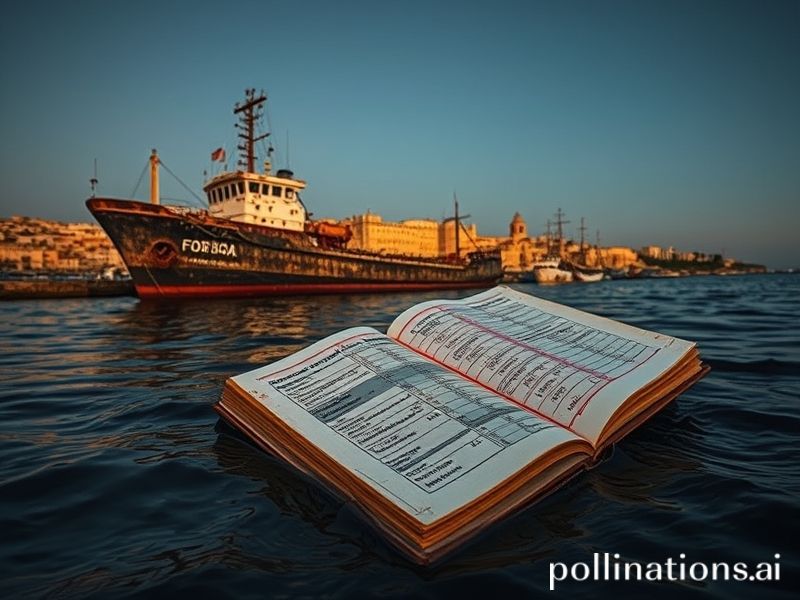

Fortina’s €10 million bill: How Sliema’s floating pools sank Malta’s public purse

Fortina and the real cost to the State

By Hot Malta Staff

The first time most Maltese children see Fortina, it is from the upper deck of a yellow school bus crawling along the Tigné seafront: a jagged white wall that looks as if someone has glued a slice of Miami to the edge of Valletta’s 16th-century bastions. To them it is simply “il-post fejn għandhom il-pixxina fuq il-baħar” – the place with the pool that floats on the sea. To the rest of us it has become a shorthand for every argument about over-development, public land, and who exactly picks up the tab when the tide – literal and political – comes in.

This week, Environment Minister Miriam Dalli confirmed what NGOs have been shouting for years: the State will have to foot at least €7 million to dismantle the illegal concrete platforms that prop up the Fortina chain’s lido complex in Sliema. Another €3 million may be needed to reinforce the seabed once the structures are gone. In a country where the average annual health budget per citizen is €1,850, that is the equivalent of 5,400 hospital visits vanishing into the waves. The figure does not include the decade of legal fees paid by the Attorney General’s office, nor the lucrative 2005 emphyteusis that allowed the developers to lease public seabed for €1.50 per square metre per year – less than the price of a pastizz.

Walk along the Sliema front at 6 a.m. and you will see the real cultural footprint of Fortina. Elderly men still arrive with folded towels and metal flasks, hoping to claim a patch of smooth rock before the lido guards unroll the red-carpet rope that signals “private”. “We used to swim here before the war,” says 83-year-old Ċensu Galea, pointing to a slab now painted with the Fortina logo. “My father fished octopus under those very steps. Now if I sit on them I am told I need a €30 day pass.” The irony is thicker than the summer jellyfish bloom: a nation that prides itself on welcoming strangers has cordoned off its own shoreline to its pensioners.

The Fortina story is also a family saga. The original 1960s hotel was a modest four-storey block built by the Psaila family, Sliema butchers who spotted tourism’s potential early. Thirty years later, their heirs teamed up with Libyan investors and unveiled a six-storey spa, two lagoon pools on stilts, and a marketing campaign that promised “Las Vegas meets the Mediterranean”. Planning Authority files show 18 enforcement notices issued between 1997 and 2021; each one was appealed, suspended, or quietly archived. In Malta, enforcement has become a sort of national limbo dance – how low can you go before someone notices?

Local businesses feel the knock-on. “Cruise-liner passengers see the aerial shots on Booking.com and think the whole coast is a resort,” says Sarah Camilleri, who runs a tiny kiosk selling ħobż biż-żejt opposite the lido. “They don’t wander up to Tower Road for lace or a bottle of Kinnie. They stay inside the Fortina bubble.” Data from the Malta Tourism Authority backs her up: all-inclusive occupancy on the Sliema peninsula has risen 42 % since 2015, while average spend in surrounding shops has dropped 19 %. The State earns VAT on the room rate, but the neighbourhood loses the multiplier effect of every cappuccino that is never bought.

Then there is the ecological bill. Marine biologist Prof. Alan Deidun calculates that the shaded seabed beneath the platforms has lost 70 % of its Posidonia oceanica, the seagrass that keeps our water crystal clear and our fish stocks alive. Replacing it will take at least 50 years – longer than the lease the developers originally signed. “We are literally paying three times,” Deidun says. “Once in environmental degradation, once in legal subsidies, and now in clean-up costs.”

So when ministers promise that demolition will start “within months”, scepticism is understandable. We have been here before: the 2018 Mrieħel towers, the 2020 db project in St George’s Bay, the 2022 Żonqor university that never was. Each time, the pattern is identical: outrage, inquiry, amnesty, repeat. Fortina may yet survive if yet another “comprehensive redevelopment” application lands before the bulldozers do. After all, the temporary structures were supposed to be “interim” in 2004.

What is at stake is not just €10 million of public money, but the soul of a coastline that belongs to everyone who has ever dived off a yellow limestone block, sold pastizzi to sunburned Brits, or proposed marriage on a luzzu rocking gently at sunset. If we cannot defend 180 metres of seabed in full view of Parliament, what hope is there for the hidden valleys of Gozo or the silent cliffs of Wied Babu?

The real cost to the State, then, is not measured only in euros. It is measured in the slow erosion of trust – the quiet resignation that the next generation will inherit a country where every rock, every wave, every sunset glow carries a barcode. And that price, unlike a concrete platform, cannot be demolished overnight.