Malta’s Back-to-School Wake-Up Call: Why Teacher Well-Being Shapes the Whole Island

Back to school: the importance of educators’ well-being

By Hot Malta Staff

Valletta – While parents scramble for stationery deals in Hamrun’s back-to-school markets and children compare rainbow-coloured lunchboxes, a quieter conversation is unfolding in staffrooms across the archipelago: how are the teachers themselves doing?

This year, Malta’s 7,700 state-school educators return to classrooms still echoing with the pandemic’s aftershocks—mask stockpiles in cupboards, tablets charged for new digital textbooks, and, less visible, the psychological residue of two years in survival mode. A recent University of Malta survey found that 62 % of local teachers report “high emotional exhaustion,” a figure that dwarfs the EU average of 37 %. Yet, beyond the statistics, the issue cuts to the heart of Maltese society, where the village school has long doubled as a civic heartbeat.

“Look at Żebbuġ Primary,” says Antonella Falzon, president of the Malta Union of Teachers. “It’s not just a building; it’s where festa costumes are sewn, where pensioners learn basic IT, where neighbours meet for kafe’ during break.” When teachers burn out, she argues, the ripple is felt at band club meetings, in parish confession queues, even in the village bakery at 5 a.m. “A frazzled educator means a frazzled community.”

Cultural weight

Malta’s compact size intensifies the bond. On an island where everyone is two degrees of separation from their Year 4 teacher, educator well-being is personal. Grandmothers who once recited times-tables to their grandchildren now watch those same grandchildren FaceTime a teacher at 9 p.m. for homework help. The pandemic normalised such blurred boundaries, but it also normalised 12-hour workdays and Whatsing voice notes from parents at midnight.

Education Minister Clifton Grima insists change is afoot. September marks the national roll-out of the “Well-being Toolkit,” a €1.2 million programme co-designed with educators themselves. Every state school will gain one “well-being promoter” released from two teaching periods weekly to organise mindfulness sessions, peer-support circles and, crucially, gate-keeping for professional counselling. “We cannot demand excellence from students if we tolerate exhaustion in those who teach them,” Grima told reporters outside Saħħan Nursery School in Msida.

Yet scepticism lingers. At a humid August meeting in Floriana, 300 educators gathered to quiz officials on workload caps. Primary teachers still juggle 28 contact hours, among Europe’s highest, while learning support educators (LSEs) often split their week between three schools, navigating traffic-snarled roads from Mellieħa to Marsaxlokk. “A promoted post comes with €7 weekly before tax,” one LSE quipped, prompting weary laughter.

Community solutions

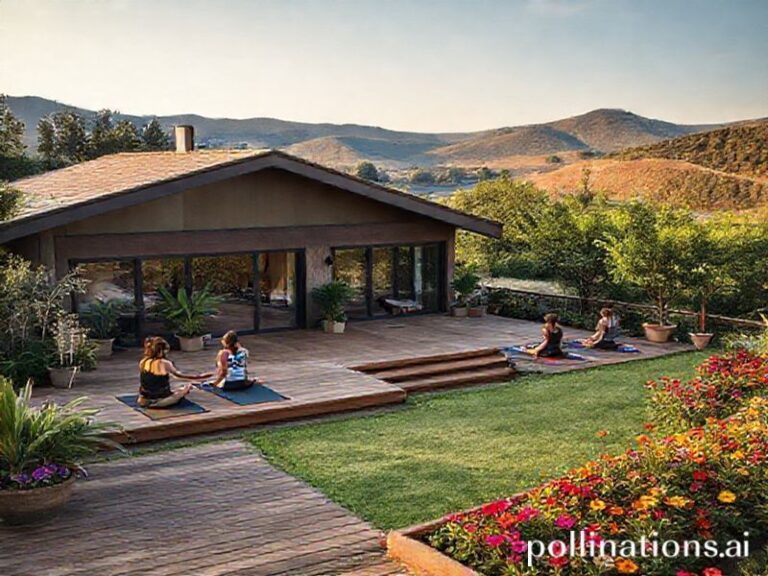

Creative fixes are emerging from the ground up. In Għargħur, the parish priest donated an unused storeroom converted into a “quiet cocoon” where staff decompress between lessons—think dimmable lamps, yoga mats and the faint scent of locally grown lavender. Attendance is voluntary, but the waiting list is already three weeks long. Meanwhile, Sliema’s Stella Maris College trialled “family-style” lunches: teachers and students eat together, phones banned, fostering relationships that cut behavioural incidents by 18 % last year.

Businesses are waking up. Pastizzi kingpin Sphinx is offering free breakfast to any educator flashing a staff badge during the first month of term, while ride-hailing app eCabs created a “Teacher Tuesday” 20 % discount code after internal data showed educators are the profession most likely to work through lunch. Small gestures, perhaps, but in a country where the cost-of-living index has jumped 14 % since 2020, every euro counts.

The mental-health angle

Dr Marvin Formosa, director of the University of Malta’s Centre for Ageing Research, warns that ignoring educator burnout now will cost more later. “Chronic stress is linked to cardiovascular disease and early retirement,” he notes, flagging that Malta already spends €40 million annually replacing teachers who leave prematurely. “Investing in well-being is not woolly; it’s economic.”

Back in Valletta, trainee teacher Maria Camilleri, 22, is enjoying a final iced coffee before her first posting at St Albert the Great College. She admits she’s nervous, but heartened by new policies that limit weekend emails and guarantee one meeting-free afternoon per week. “My old maths teacher, Mr Pace, taught me that Malta runs on relationships,” she smiles. “If we look after the teachers, the teachers will look after the island.”

Conclusion

As the 8 a.m. bell rings next week, the focus will rightly be on children in crisp uniforms reciting the Lord’s Prayer over crackly intercoms. Yet behind every confident multiplication recital or science experiment gone gloriously wrong stands an adult who also needs care. In Malta, where classrooms double as community living rooms, protecting educator well-being is not a perk; it is the keystone of national resilience. The chalk may be smart-boards now, but the lesson endures: a healthy teacher equals a healthy Malta.