Valletta Market Canopies Must Come Down, Ombudsman Rules—Heritage vs Hawkers Showdown Looms

**Ombudsman Slams “Illegal” Suq tal-Belt Canopies, Orders Immediate Removal**

Valletta’s iconic open-air market has found itself at the centre of a fresh storm after the Ombudsman ruled that the jutting canvas canopies shading Suq tal-Belt stalls are illegal structures that must come down. In a blunt report delivered to Parliament on Tuesday, Ombudsman Anthony C. Mifsud said the covers—erected piecemeal over the past decade—violate both the capital’s 1992 conservation brief and the 2016 market concession agreement, creating “a visual and legal eyesore” in a UNESCO World Heritage zone.

The finding ends years of finger-pointing between Valletta market hawkers, the Lands Authority and concessionaire ‘Malta Markets Ltd’, and leaves new Local Government Minister Jo Etienne Abela with a hot potato: enforce the removal and risk uproar from generations-old traders, or ignore the Ombudsman and undermine rule-of-law rhetoric that the Labour administration has been trumpeting since 2013.

### Awnings that grew like weeds

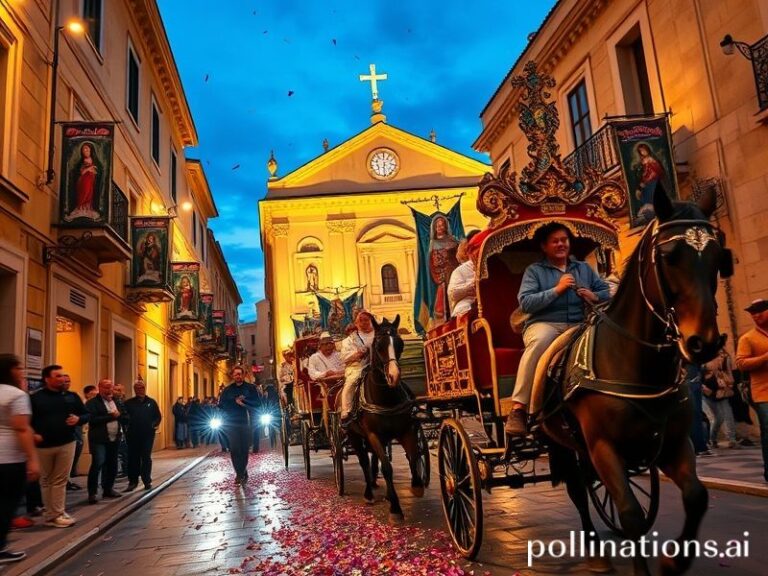

Suq tal-Belt, the daily open market that unfurls along Merchant’s Street from City Gate to Republic Square, is as Maltese as pastizzi. Grandmothers haggle over lace tablecloths; tourists snap selfies beside pyramids of prickly pears; politicians press the flesh on Saturday mornings. But the cheerful chaos masks a legal grey zone. After the 2015–18 City Gate renovation project funnelled cruise-ship crowds straight onto Merchant’s Street, stallholders began bolting retractable awnings to baroque façades, arguing that July sun and December drizzle were killing trade. No permits were filed; no enforcement followed. What started as two or three modest sheets metastasised into a rainbow of tarpaulin, PVC and, in one case, a bespoke retractable roof complete with drainage pipes.

### “Heritage hijack”

The Ombudsman’s investigation, triggered by a 2021 complaint from heritage NGO Flimkien għal Ambjent Aħjar, concludes that the canopies “arrogate public airspace” and obscure architectural features such as carved limestone cornices and wrought-iron balconies. Photographic evidence attached to the 42-page report shows 48 separate structures, 37 of which extend beyond the two-metre legal threshold for temporary shading. “Every day these illegalities remain,” Mifsud writes, “the State is complicit in normalising abuse inside a Grade 1 scheduled street.”

### Hawkers: “We’ll be roasted alive”

News of the impending removal sparked panic among the market’s 170 licensed hawkers. “Without shade my tomatoes turn to soup by 10 a.m.,” says 67-year-old Joe Borg, whose family has sold fruit on the same corner since 1958. “Will the Ombudsman compensate my rotting stock?” Others fear a domino effect. “First the canopies, then they’ll say our wooden stalls are ‘visual clutter’,” warns hawkers’ union secretary Marlene Mizzi. The union claims 60% of vendors are over 55 and unwilling to relocate to the air-conditioned, rent-paying Suq tal-Belt food hall across the street, arguing the €7 daily pitch fee is the only thing keeping pensioners solvent.

### City’s double dilemma

Mayor Alfred Zammit faces a classic Maltese Catch-22. “Valletta 2018” EU Capital of Culture cash may have polished the stone, but empty shopfronts still pockmark side streets. “Tourists come for ‘authenticity’—the smell of strawberries, the banter,” Zammit told Hot Malta. “If we sanitise too much we become another outdoor mall.” Yet the capital’s new pedestrian-first strategy, unveiled last month, pledges to “declutter public realm” ahead of the 2026 Valletta Green Festival. Removing the canopies would score quick heritage points, but could also drive vendors—and their bargain-hunting clientele—into the suburban open-air markets of Birkirkara or Fgura, sapping footfall from capital cafés still recovering from COVID-19.

### What happens next?

The Ombudsman’s ruling is not legally binding, but ignoring it would invite judicial review. Minister Abela has 30 days to respond; sources say a compromise “sun-sail” scheme—uniform, beige, retractable at night—is being floated, though heritage NGOs insist only zero-coverage is acceptable. Enforcement officers have already tagged each canopy with fluorescent stickers, a sight that triggered a heated argument on Facebook group ‘Valletta Daily’ between those cheering “about time” and others branding officials “heritage fascists”.

### Conclusion

For generations of Maltese, a wander down Merchant’s Street is a tactile link to childhood Saturdays clutching mum’s hand, the scent of peaches mingling with church incense from the Jesuit dome overhead. The canopies may be illegal, but they have also become part of the living city—patchwork parasols shielding both produce and tradition. Tearing them down without offering dignified, practical alternatives risks turning a heritage victory into a social wound. The challenge for authorities is not simply to enforce the letter of the law, but to recognise that Valletta’s soul is stitched from the very fabric now under threat. Rule of law must prevail, yet so must empathy; otherwise the only shade cast will be the long shadow of a city that forgot who it was protecting its stones for.