Isabel Allende’s Exile Story Finds Surprising Home in Malta’s Migration Conversation

**Watch: Isabel Allende – A Writer in Exile, A Beacon for Malta’s Own Stories of Displacement**

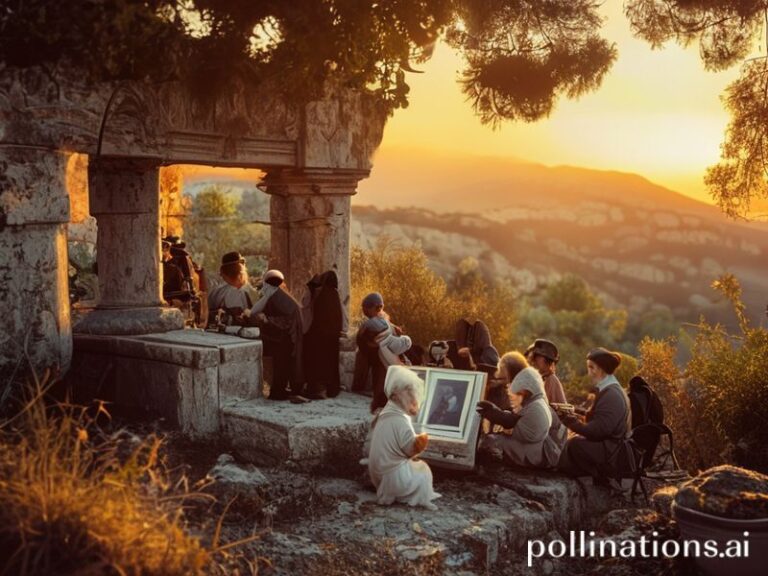

Valletta’s historic streets have long echoed with tales of exile—from the Knights who sought refuge on these limestone shores to modern-day migrants crossing the Mediterranean. It’s against this backdrop that Isabel Allende’s documentary *A Writer in Exile* finds unexpected resonance in Malta, screening to a packed house at Spazju Kreattiv last Friday night.

The Chilean-American novelist, who fled her homeland after the 1973 military coup, has become an unlikely touchstone for Malta’s own communities of displacement. As local writer and activist Leanne Ellul noted during the post-screening discussion, “Allende’s story isn’t just Latin American history—it’s our history too. Every boat that arrives here carries someone’s unfinished manuscript.”

The documentary, which traces Allende’s journey from Santiago to Caracas to California, struck a particular chord with Malta’s Latin American diaspora. Roughly 1,200 Chileans, Argentinians, and Uruguayans now call the islands home, many arriving via Italy during the 1970s dictatorships. Maria Gonzalez, 68, who fled Buenos Aires in 1976, wiped tears during the screening: “She’s telling my mother’s story. The same mother who never learned English, who died in Għaxaq still dreaming in Spanish.”

What makes Allende’s narrative especially relevant to Maltese audiences is her treatment of language as homeland. When the author describes writing her first novel as “rebuilding Chile in words,” murmurs of recognition ripple through the crowd. Malta’s own linguistic exiles—those who’ve watched their children lose Maltese fluency, or who’ve switched to English for economic survival—understand this intimately.

The screening, organized by local NGO Integra Malta and the National Book Council, represents a growing cultural shift. As literary curator David Aloisio explains, “We’re moving beyond the Mediterranean insularity that defined Maltese literature for centuries. Allende shows us that exile isn’t just physical—it’s lexical, emotional, generational.”

This expansion mirrors Malta’s evolving identity. With 22% of residents now foreign-born, the islands are grappling with what it means to be Maltese in an age of mobility. Allende’s meditation on hybrid identity—she calls herself “a vegetarian Chilean who speaks Spanish like a Peruvian and thinks like a Californian”—offers a framework for local children of mixed heritage who’ve never felt fully Maltese nor fully foreign.

The impact extends beyond literary circles. At the University of Malta, Professor JosAnn Cutajar’s sociology students are using Allende’s concept of “nostalgia utopia”—the longing for a perfect past that never existed—to analyze Maltese emigrant communities in Australia and Canada. “It’s reframing how we understand our own diaspora,” Cutajar notes. “The Maltese who left in the 1950s aren’t just economic migrants—they’re cultural translators, like Allende.”

Local publishers are taking note. Merlin Publishers has just acquired rights to *Violeta*, Allende’s latest novel, with plans for a Maltese translation—the first of her works in the national language. Translator Toni Sant argues this isn’t just literary tokenism: “Translating Allende into Maltese is an act of cultural assertion. We’re saying our language can carry the weight of universal exile.”

The documentary’s timing proves serendipitous. As Malta debates migration policy and EU burden-sharing, Allende’s humane portrayal of displacement offers counter-narrative to headlines about “migrant influx.” When she declares “borders are scars on the earth,” the audience at Spazju Kreattiv erupts in applause—including several Maltese citizens who arrived as refugees themselves during World War II.

As the credits roll and the crowd spills onto St. Christopher Street, something shifts. A young Maltese woman approaches two Syrian women who’d attended the screening. “Would you like to join our book club?” she asks. “We’re reading Allende next month—in English, Arabic, and Maltese.”

In that moment, Valletta’s limestone walls seem less like barriers and more like pages waiting to be written. Allende’s exile, it turns out, has found an unexpected home—in a nation still learning that every story of displacement carries the DNA of humanity’s shared narrative.