From BMWs to bus-lane briefings: How Malta’s ex-top cop turned a car dealer into his ‘MI5’

# Ex-police commissioner says he used car dealer to ‘gain’ information: A very Maltese tale of power, petrol-heads and parish-whispers

Valletta – When Lawrence Cutajar took the witness stand on Tuesday and admitted he had used a Sliema car-dealer as an unofficial “ears on the street”, half the island nodded in recognition. In Malta, the village *kappillan* and the neighbourhood *karozzin* salesman have always traded in the same currency: gossip that moves faster than a Gozo ferry in peak August. What shocked the courtroom was not the admission itself, but that a former police commissioner had formalised what every *ż**iju* at the *każin* claims he can do better than Europol.

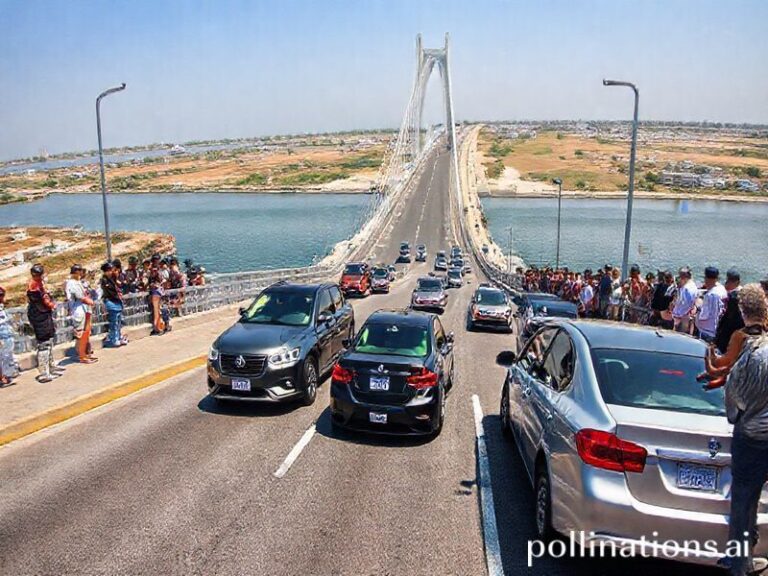

Cutajar, 63, told the public inquiry into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia that between 2016 and 2019 he met “at least 30 times” with Yorgen Fenech’s middle-man, car importer Silvio Valletta (no relation to the capital), to “receive background” on everything from fuel smuggling to money-laundering. The pair’s preferred HQ? The now-shuttered *Café du Brazil* on Tower Road, where elderly Sliema residents still remember Valletta parking his matte-black G-Class in the bus lane while inside, over *espressi* paid for in cash, the nation’s top cop and the man who supplied half the island’s BMWs swapped notes like two *kantini* regulars dissecting last night’s *serata*.

To outsiders, the image of a police chief leaning on a car salesman for intel feels surreal. On the archipelago, it is almost folklore. Maltese policing has always borrowed from parish networks; the *pulizija* who grew up on the same cobblestones as the crooks he now chases. Cutajar’s defence—that Valletta “moved in circles I could never penetrate”—rings true in a country where your first communion cohort doubles as your LinkedIn. Yet the spectacle of a commissioner outsourcing state intelligence to a man whose showroom doubled as a backdrop for *Tista’ Tkun Int* selfies has reopened a wound that never quite scabs over: the suspicion that rules here are written in pencil, then rubbed out with an oily rag.

Inside the courtroom, the mood was part *sutta*, part *surreal*. Lawyers in black robes fanned themselves with the *Times of Malta* as Cutajar explained how Valletta’s “access to Libyan number-plates” helped track fuel smugglers. A pensioner from Paola in the public gallery whispered to her neighbour: “*Mela* that’s why my nephew’s *barkazz* got stopped last Easter—Silvio rang the *kummissarju*!” The neighbour replied, louder than intended, “*U ejja*, my cousin *knew* the diesel was cheaper in Marsa.” Even the judge smirked.

Outside, the reaction split along generational lines. Older Maltese shrugged: *“Xiġġu, that’s how we’ve always policed the sea between here and Tunisia.”* Younger voters, weaned on *Occupy Justice* vigils and Reddit threads, saw confirmation that the 2010s were a lost decade where the line between state and *klandestin* blurred like diesel on harbour water. “It’s not just Cutajar,” 24-year-old law student Maria Pace told *Hot Malta* outside the law courts. “It’s the whole *sistema* that thinks *‘ħobża* and a phone-call’ beats due process.” Her friend held a placard: *“Your mechanic should not be your MI5.”*

The testimony also landed badly in an economy that still celebrates the *xufier* as folk hero. Maltese men define themselves by what they drive; licence-plate numbers are stored in mental *filofaks* next to nicknames and village allegiances. To discover that the man who sold you your 320d may have been filing a parallel logbook for the police feels like learning your *barber* keeps notes on your hairline for the Inland Revenue. Trust, already dented by *17 Black*, Pilatus and *żibel* everywhere, took another tyre-iron to the chassis.

Tourism operators worry the headlines feed a caricature of Malta as *Sicily-with-kimchi*, where *“everything is for sale, even the police”*. Yet the story is irresistibly local: the café where Cutajar and Valletta met is 200 metres from the *Dragonara* casino, where British stag parties now pose for Instagram, oblivious that the pavement once hosted a real-life *Commissario Montalbano* episode scripted in *Maltenglish*.

What happens next? The inquiry will trudge on, but the anecdote has already joined the national anthology: *“Remember when the commissioner used the BMW guy as Google?”* Expect it at *festa* bars, on *net-tv* phone-ins, in sermons where priests decry *“il-korruzzjoni tal-lum”*. Because in Malta, every scandal eventually becomes a *ħaġa normali*, retold with the same shrug reserved for traffic on the *Santa Luċija* roundabout.

Cutajar left court flanked by lawyers, refusing questions. Outside, a teenager on a *pedal-kart* circled the Triton Fountain yelling *“Silvio, għandi x’inġiblek!”*—a punch-line before the inquiry even publishes its conclusions. The rest of us drive home, eyeing the rear-view mirror, wondering who is taking notes at the next petrol station.