Trident Estates’ €6.7M Profit Sparks Hope and Debate Across Malta

Trident Estates, the company that turned a derelict 18th-century hospital in Sliema into Malta’s most Instagrammed seafront façade, has posted a 12 % jump in half-year profit to €6.7 million – a figure that matters far beyond the balance sheet of a single developer. In a country where every square metre of limestone seems to carry the weight of family memory, the announcement rippled through coffee-shop chatter last weekend like the scent of pastizzi fresh from the oven. “They’re making money again,” nodded Ġorġ, 71, nursing a glass of Kinnie on the Tigné seafront. “Let’s hope they remember who still swims here.”

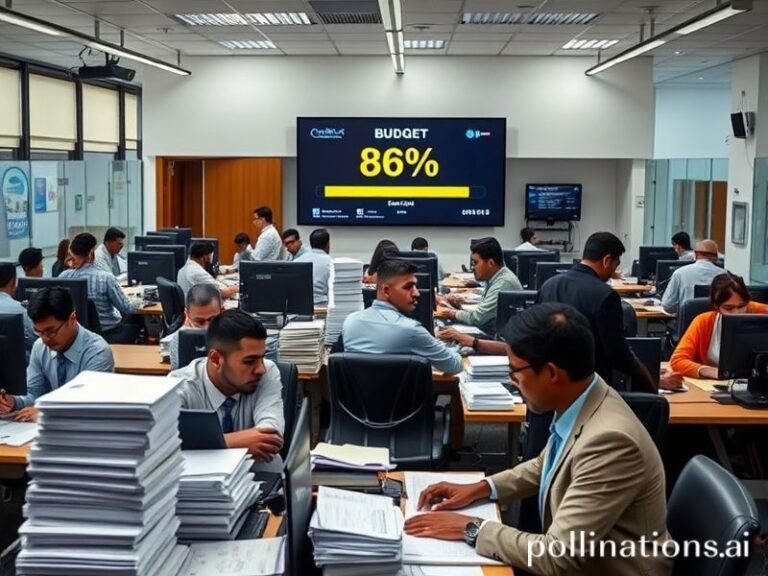

The numbers, released after Tuesday’s close of trading on the Malta Stock Exchange, show rental income from Trident’s retail and office portfolio climbing to €9.4 million, driven largely by full occupancy at The Point shopping mall and renewed leases at the iconic Fort Cambridge apartments. CEO Mark Portelli told analysts that footfall at The Point is now “north of 14 million annually – the equivalent of every Maltese citizen walking through 28 times a year”. Locals smile at the statistic, knowing half those visits are teenagers cooling off in air-conditioned corridors during August’s sweltering festa season.

Yet the profit surge arrives against a backdrop of national soul-searching. Over the past decade, Sliema’s skyline has erupted into a chess set of glass towers, sparking petitions, pastoral letters and the odd cheeky protest banner: “Enjoy the view – while it lasts.” Trident, majority-owned by the family behind Malta’s largest supermarket chain, is both protagonist and punch-bag in that narrative. Its 2013 transformation of the old St. Patrick’s military hospital into the Fort Cambridge mixed-use complex was hailed as a masterclass in adaptive reuse; critics still mourn the loss of the hospital’s wartime murals, now preserved only in black-and-white postcards sold at weekend flea markets.

Inside the company, executives insist the latest figures allow them to “give back”. A €250,000 community fund – financed entirely by the half-year surplus – will restore the façades of four baroque town-houses in nearby Gżira, including the crumbling birthplace of 19th-century poet Dun Karm Psaila. “Heritage is our true luxury brand,” Portelli said, quoting a line he admits borrowing from Tourism Minister Clayton Bartolo. Work starts in October, just as the village festa winds down and the statue of the Madonna is hoisted back into her niche.

For tenants, the boom translates into confidence. Sarah Galea, 27, opened her zero-waste refill store, “Bring Your Own Jar”, at The Point last January, betting that eco-conscious shoppers would brave shopping-mall parking. “Footfall is insane,” she laughs, stacking paper-wrapped Marseille soap. “When Trident wins, small weird businesses like mine get shelf space.” Across the corridor, 68-year-old Saver Sciberras has sold traditional Maltese lace from the same kiosk since 2010. He is more circumspect: “Rent is tied to turnover – if they earn more, my slice gets bigger, but so does the bill.” Still, he has just employed his granddaughter part-time, the fourth generation to handle bobbins in the family.

Not everyone is toasting the windfall. Housing advocacy group Moviment Graffitti points out that apartments at Trident’s completed “Fortress Gardens” block start at €750,000, pricing locals out of their own peninsula. “Profit is measured in euros, but the loss is measured in displaced families,” spokesperson Andre Callus said. Government data shows Sliema’s average property price has doubled since 2016, while median salaries rose barely 15 %. The dichotomy fuels gallows humour on Facebook: “Soon we’ll need a Trident loyalty card to afford sunlight.”

Economist Stephanie Fabri argues the solution lies in policy, not pillorying individual firms. “Real-estate companies maximise shareholder value; that’s their job. The failure is ours if we don’t tax secondary dwellings or incentivise affordable stock.” She notes that Trident’s increased profit will yield €1.1 million in additional corporate tax – enough, theoretically, to finance 25 social housing units if channelled through the Housing Authority.

Meanwhile, the company is quietly buying rooftop rights above neighbouring blocks, sketching plans for sky-gardens linked by glass bridges. Renderings leaked to Lovin Malta show infinity pools cantilevered over the church dome of Stella Maris, a vision that sent parish priest Fr. Joe Borg straight to the Planning Authority objections desk. “We welcomed them when they restored our chapel bell,” he told Hot Malta. “But now they want to build in the sky above it. Even God needs breathing space.”

As the harbour ferry hoots its 7 p.m. departure and tourists selfie against a sunset the colour of ħobż biż-żejt tomatoes, Trident’s improved profit feels less like a ledger entry and more like a Maltese Rorschach test. Some see jobs, polished façades and a reason to keep believing in public-company accountability. Others see a gilded gate closing on the Malta they knew. Either way, the limestone keeps bearing witness, and the sea – for now – remains free.