Mini Malta, Major Stand: How the Island Nation Is Championing a Special Tribunal for Ukraine

From the honey-coloured bastions of Valletta to the narrow, sun-bleached alleys of Mdina, talk of a “special tribunal for Ukraine” is no longer a distant diplomatic echo. Over cups of strong Maltese tea at Café Cordina and on the shaded benches of Upper Barrakka Gardens, islanders are weighing the implications of a proposed international court that could try the crime of aggression against Ukraine. For a nation whose own history is stitched together by sieges, knights, and foreign dominion, the idea of holding aggressors to account resonates far beyond the Mediterranean.

Malta’s government—currently a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council—has quietly but firmly backed the push for an ad-hoc tribunal, arguing that impunity anywhere is a threat to the rule of law everywhere. Foreign Minister Ian Borg told the General Assembly in New York last month that “small states understand best how fragile sovereignty can be; we therefore carry a moral duty to strengthen it.” Back home, the statement landed like a għana ballad, stirring both pride and debate: can a country of barely 500,000 souls truly influence global justice?

Walk into any kazin in Għaxaq or Żabbar after Sunday Mass and you’ll hear farmers and band-club enthusiasts parsing the issue with the same fervour they reserve for festa fireworks. Eighty-one-year-old Karmenu Briffa, who still remembers the 1942 convoys that saved Malta from starvation, puts it bluntly: “If Hitler’s men had faced a tribunal in ’42, maybe we’d have been spared the bombs.” His granddaughter Martina, a third-year law student at the University of Malta, volunteers with local NGO aditus foundation, translating Ukrainian war-crime testimonies into English. “Malta survived because others stood up,” she says, eyes fixed on the baroque skyline. “Now we stand up for others.”

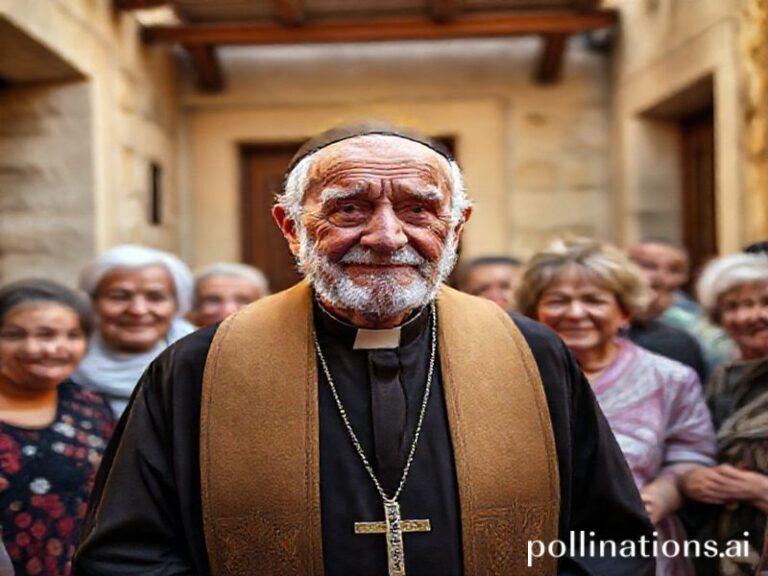

Cultural memory runs deep here. The knights of St John once lit bonfires on Dingli Cliffs to warn of Ottoman fleets; today, NGOs project blue-and-yellow lights onto the same cliffs in solidarity with Kyiv. The contrast is not lost on Archbishop Charles Scicluna, who last Easter prayed for “a Europe where borders are respected, not redrawn by tanks.” His sermon was streamed to Ukrainian refugees living in the Hal Far open centre, where 47 displaced families have woven new lives amid Malta’s limestone villages.

Economically, the tribunal debate is already rippling through the island. Maltese law firms specialising in international arbitration—firms like Ganado Advocates and Fenech & Fenech—report a surge in Ukrainian clients seeking advice on asset recovery. Meanwhile, gaming giants headquartered in St Julian’s have pledged micro-donations from every online poker pot, raising over €1.2 million for Ukrainian legal aid. Even the traditional lace-makers of Gozo are stitching blue-and-yellow motifs into their bizzilla, selling the pieces at the Citadel to fund war-trauma therapy for children.

Critics, however, warn against moral grandstanding. Opposition MP Adrian Delia questions the cost of hosting tribunal hearings in The Hague when Malta’s own courts face chronic backlogs. “Charity begins at home,” he insists, pointing to 4,000 pending domestic violence cases. Yet civil society pushes back. The Malta Chamber of Advocates has offered pro bono research support, arguing that strengthening international law ultimately strengthens Malta’s own jurisdiction.

In the coming weeks, Valletta will host a closed-door seminar for Baltic and Balkan diplomats on how small states can shape tribunal rules of evidence. The venue? The old Sacra Infermeria, where knights once tended to wounded soldiers, now a conference centre. Organisers say the symbolism is deliberate: centuries ago, Malta gave shelter to the displaced; today it can give shelter to the very idea of justice.

As the sun sets over Grand Harbour, the mood is one of cautious optimism. Fishermen mend nets beneath the watchful gaze of Fort St Angelo, while teenagers stream Ukrainian folk songs on TikTok from the Sliema ferries. Whether the special tribunal ever sits in Malta or thousands of kilometres away, the island has already rendered its verdict: sovereignty is sacred, aggression must be answered, and even the smallest voice can carry across the waves.